REMEMBERING LEONG TAT CHEE

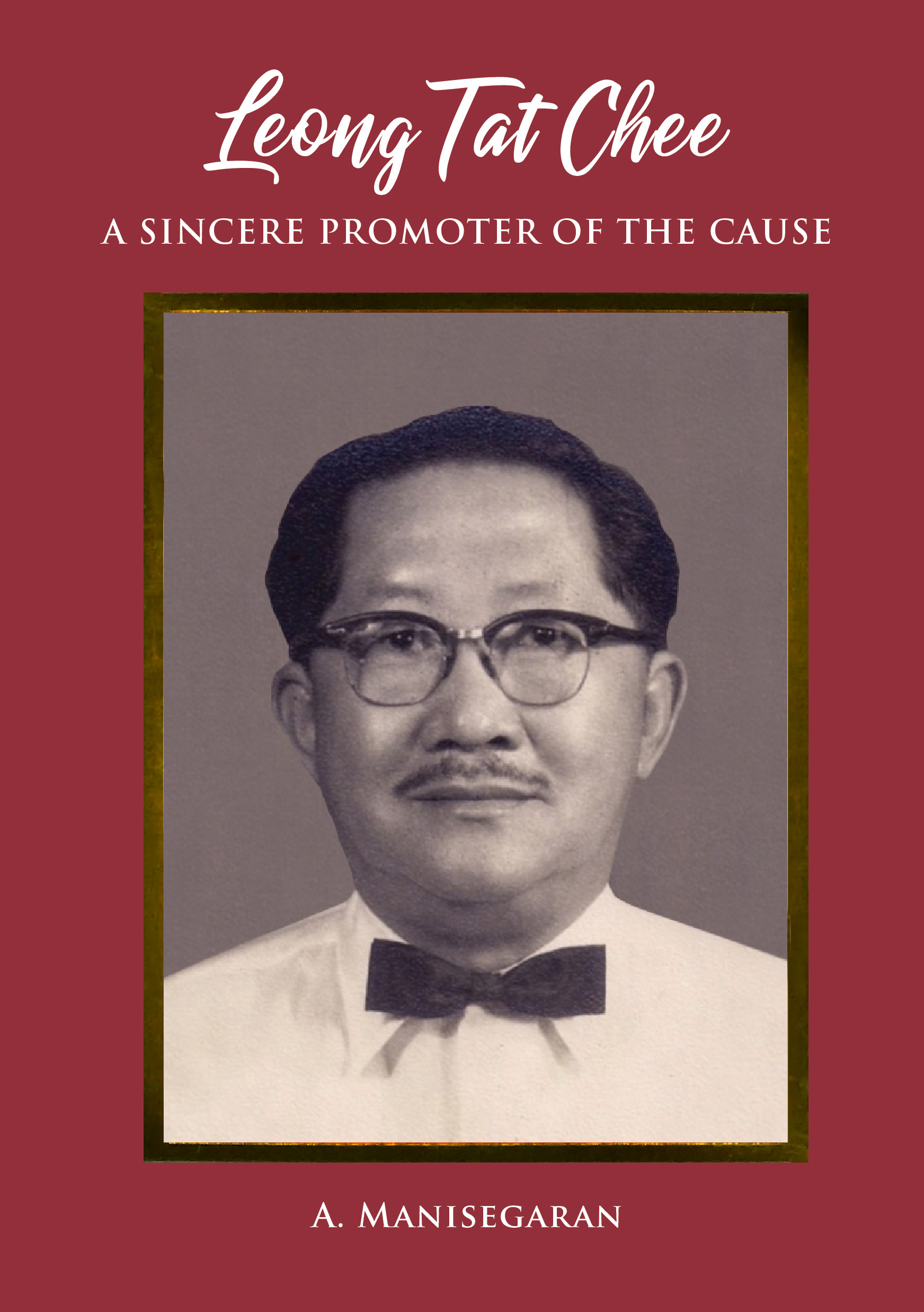

Leong Tat Chee – A Sincere Promoter of The Cause

A book in remembrance of Leong Tat Chee has just been released and is being marketed by the Bahá’í Publishing Trust of Malaysia. This story carries some salient aspects taken from this said book.

It was through a dramatic challenge that Mr. Leong Tat Chee accepted the Faith in Malacca town and arose, meteor-like, in the service of the Cause in Malaysia. Belonging to the earliest batch of believers in Malaysia, this remarkable man gave rise to generations of his descendants whose lives, till today, revolve around the Bahá’í Faith. From the very beginning, Leong Tat Chee became very devoted to the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh and made Bahá’u’lláh the centre of his life. He was strong and courageous in his new-found religion from the start, and he never looked back.

Leong Tat Chee, his wife and family were very Chinese in their ways and were actively involved in the many festivals and traditions of ancestral worship and Buddhism, and in the activities of their local Chinese temples. At one time, Leong Tat Chee was President of the Chan Hoon Teng Temple. Later he became a Trustee and head of the Swastika Society – an organization which combined traditions of Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, Taoism and Confucianism.

Wedding photo At the time of accepting the Faith

It was in 1954 that Leong Tat Chee chanced upon the Bahá’í Faith when he was Health Inspector with the Malacca Municipality. He saw an advertisement in the local papers regarding a fireside meeting in the home of Dr. K.M. Fozdar and his wife Shirin in Malacca town. The Fozdars were pioneers to Singapore. In 1953, the Fozdars moved to Malacca from Singapore when Dr. K.M. Fozdar was offered a job as a medical doctor at a local medical clinic. As Leong Tat Chee had an inquiring mind, he went to the meeting. The Fozdars and the Leongs soon became friends and met several times to discuss about the Faith. At these meetings that went on for months, Leong Tat Chee would often enter into heated arguments with Dr. Fozdar, and yet Leong Tat Chee was still not convinced. One day, the annoyed Dr. K.M. Fozdar declared that talking to Leong Tat Chee was like playing beautiful music to a cow! Dr. K.M. Fozdar then threw Leong Tat Chee a challenge – to read the Bahá’í books for himself. Leong Tat Chee got hold of some Bahá’í books from Dr. K.M. Fozdar and took two weeks leave from his office and locked himself in his room to read them. Upon completion of reading the books, he emerged from his room an enlightened person and accepted the Faith in early 1955. He instantly pursued his services for the Cause with unstinting zest.

As soon as Leong Tat Chee accepted the Faith he changed his old habits, first by giving up his ‘mah-jong’ games with his friends. He began applying Bahá’í principles in his life and at the workplace, he engaged in consulting with those working under his supervision. He would also often invite them to his home. He was a chain smoker as well. When he came across the Tablet of Purity by Abdul Baha in which the danger of smoking tobacco is mentioned he quit smoking immediately and altogether. In 1955, Leong Tat Chee was elected on to the first Local Spiritual Assembly of Malacca and became its Chairman. He soon emerged as a fatherly figure to the believers in Malacca town, and to the many Bahá’ís in Malaysia.

He then taught his family members, and all of them accepted the Faith in stages. Mrs. Leong became a believer on 25 December 1957. Within two days of Mrs. Leong accepting the Faith. the first Pan-Malayan Summer School for Malaya was held in Malacca. There Mrs. Leong volunteering along with her husband in going the local markets, cooking and serving the friends at this first summer school. The couple continued to volunteer to be the chief cooks at all the early summer schools, though managing the kitchen was not an easy job. They did this service for many years- to be of service to the servants of the Faith.

Leong Tat Chee believed fully in practicing the teachings of equality between the sexes. Leong Tat Chee himself nurtured her in the Faith, as he believed a wife has a strong role in a husband’s services. Mrs. Leong becomes a wonderful Bahá’í providing great hospitality and was also a strong supporter of her husband’s teaching activities. She would open her house to believers and non-believers alike since her house was serving the role of a Bahá’í Centre. Whenever she had the opportunity she joined her husband in his teaching trips to estates where the rubber tappers kept cows and other farm animals and where the sanitation was not good, attracting a lot of flies. She often came back with insect bites but never complained.

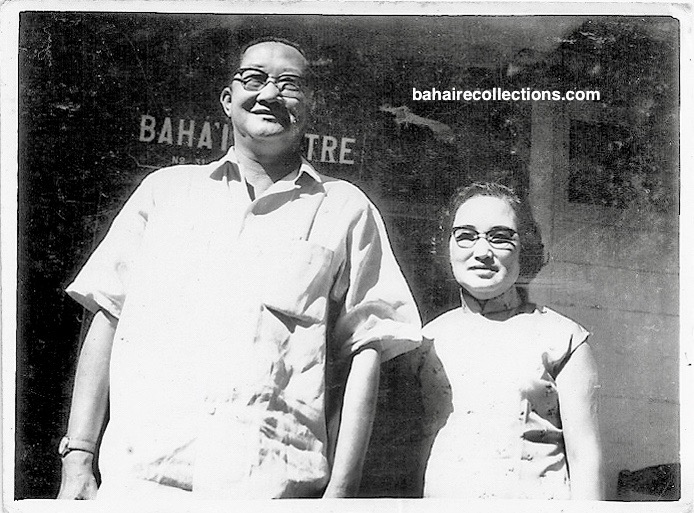

His wife- his strongest supporter

The change in Leong Tat Chee and his family was so dramatic that their relatives and their Chinese community began to ridicule them and to a great extent ostracized them as they felt that they had betrayed Chinese family traditions and ancestral beliefs. They thought that Leong Tat Chee had become mad and even called him the ’mad monk’. His own brother and family who lived just a few doors away demonstrated such great hostility to him. They went so far as to say that no one would marry their daughters as they had joined this new religion. But the Leongs remained strong. By 1961 when Leong Tat Chee’s entire family had accepted the Faith they decided it was time to remove all signs of their earlier religious and cultural attachments. The family handed over the ancestral family plaque which traditionally hangs over the main entrance of a home, to his younger brother Leong Tah Quai for safe-keeping. In its place, the Leong family mounted a big, conspicuous sign that read ‘Bahá’í Centre’ in February 1962. This was again seen as a heretical act by members of his community and relatives.

Leong Tat Chee believed that the believers had to live the Bahá’í life at a time when the believers of the new Faith were under the watchful eyes of the public. He himself played the leading role in deepening the believers from the early days. He started buying Bahá’í and collecting as much Bahá’í literature as possible. He read them thoroughly to get a good understanding of the content. He also paid careful attention to what visiting Bahá’ís from overseas had to say and absorbed their lessons. He would use this knowledge for his deepening classes, firesides and inspire any of the friends who would drop into to visit.

Leong Tat Chee himself tried to live his life to the standards and teachings of the Faith. At a time in the early years, many early believers found it difficult to follow the law of fasting. Yet Leong Tat Chee led the way in strengthening this Bahá’í obligation into the nascent community. During the fasting period, he hosted both breakfast to start the fast. Leong Tat Chee would go out at 5 am to buy large Chinese dumplings and other foods while his wife would wake up earlier at 4 am, to begin cooking. As dawn approached, Leong Tat Chee would drive around town to pick up believers to his house to start the fast together. The routine would be repeated after work where he would drive to the homes of the Bahá’ís and bring them to his house to break the fast together. By the evening he and his wife would have prepared sumptuous meals to break the fast. This went on for many years in Malacca.

He also made sure as many as possible would attend the all Bahá’í holy days and 19 Day Feasts. Before every Feast, he would go around in his car to pick up the friends. His wife would prepare a big dinner as an attraction for the Bahá’ís who came for the Feast. Attendance would vary, from a few persons to a larger number. He hosted the Feasts for a long time until gradually more Bahá’ís started opening up their homes for the Feasts as well, a sign of the growing maturity of the Bahá’ís of Malacca. Leong Tat Chee had indeed shouldered the lion’s share of the burdens in the community.

From the days of accepting the Faith, Leong Tat Chee was a strong defender of the image of the Faith. His greatest happiness was to hear of the success stories and what hurt him most was the slightest tainting of the image of the Faith. To him, the Faith was everything. Leong Tat Chee dealt with Bahá’is and people generally with profound love and compassion, but he could be a roaring lion when it came to defending the Faith. There was an episode of an Eurasian man who frequently cycled past Leong Tat Chee’s home and observed the Bahá’í Centre signboard that hung outside the house. When Leong Tat Chee came home for lunch, he would often sit on the rattan chair outside his house facing the main road. One day, this Eurasian man, while cycling past the house, shouted ‘ular!’ (snake in the Malay language), making fun of the name of Bahá’u’lláh. The man continued his actions for a few days. One day, when the man cycled past and again yelled the same epithet, Leong Tat Chee rushed forward, grabbed him by the shirt, dragged him to the side of the road and with a baleful stare, reprimanded him, “Brother, you can call me any name you like and I don’t care. But don’t you ever disparage the name of the Manifestation of God for today.” Leong Tat Chee then let his shirt go, and the visibly shaken man was never seen cycling past the house again. Never had the Leong family seen this side in him.

The biggest crisis in the Malaysian community took place in Malacca town. In 1959, as the Faith was emerging out of obscurity there was a bitter internal crisis. The Bahá’í community of Malacca started to witness signs of estrangement among some key believers which threatened the advancement of the Faith. Leong Tat Chee devoted his entire energy in restoring the unity in the community, and by 1962, this sad state of affairs turned around and resulted in a community that became more devoted, vibrant and united. The community began revolving around Leong Tat Chee who was seen as a stabilizing pivot in the community.

Leong Tat Chee was of the firm belief that in order to be effective in the Cause one has to practice the teachings with a full heart. Three intermarriages in Leong Tat Chee’s family established that he practiced what he preached, and these were the weddings of his daughters Lily and Mary, and son Ho San to non-Chinese. Lily wanted to marry Inbum Chinniah of Ceylon Tamil origin, who was a headmaster. When Inbum approached Leong Tat Chee for consent, Leong Tat Chee said that “Had I not been a Bahá’í, I would not have allowed you to marry my daughter. As a Bahá’í, I happily give consent to this wedding.” This was at the time when inter-racial marriages were seen by many as an abomination. Another of Leong Tat Chee’s daughters, Mary Leong Wai Yoon was also to marry a Ceylon Tamil man, Dr. S. Dharmalingam. Later on, Leong Ho San, the second son of Leong Tat Chee, married Mariette, daughter of Hand of the Cause of God Mr. Collis Featherstone of Australia, in Kuala Lumpur. This was seen as a novelty and a kind of revolution in those days.

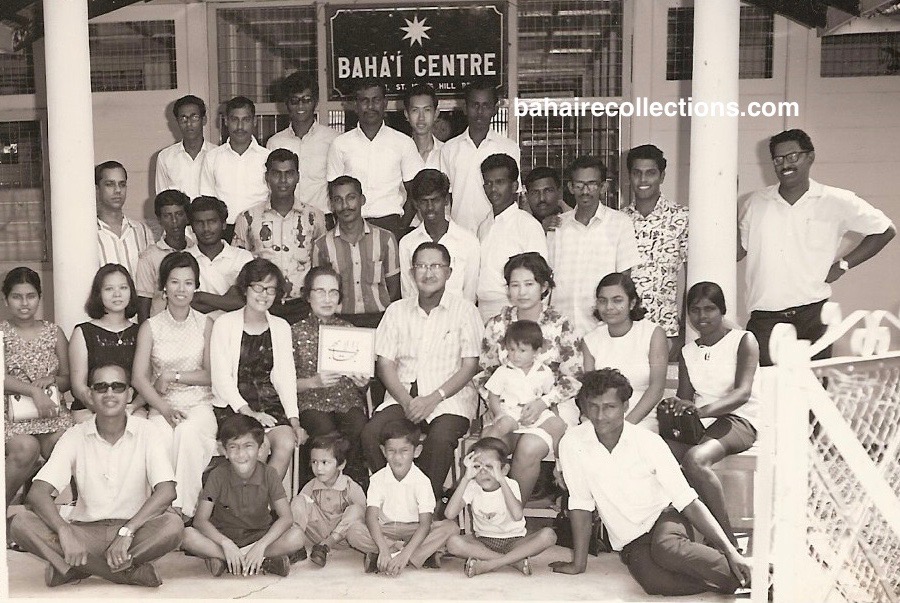

Unity in Diversity that the Leongs founded in their family.

An area of service where he dwarfed many others during his days was teaching the Cause with the greatest passion. He had a list of people of Malacca to be given the message. He went looking for them to give the message and more importantly, he always followed up. He would later take the Faith to every stratum of society and every nook and corner of Malacca town and Malacca state. When Dr. Muhajir came to Malacca in 1957, he made a personal request to Leong Tat Chee to use his car to spread the Faith to all parts of Malaya, which Leong Tat Chee gladly complied. Leong Tat Chee played a key role not only in opening up new areas for the Faith but also in the formation of the earliest Assemblies. The long list of areas that Leong Tat Chee assisted in opening up or consolidated are far too many to be mentioned. Sad to relate, many of those places have given way for urban development, and their names today remain only in history.

Believers longed to follow him on teaching trips as they came back more deepened through the discussions on the Faith that took place in the car. Leong Tat Chee would sometimes bring his wife and also some youth. As a reward for the young people who accompanied him, on the way home after a teaching trip, he would give them a treat at a Chinese restaurant or stop his car to buy fruits in season from the roadside stalls. Leong Tat Chee would often pay for the gas for the car and seldom accepted money from those who accompanied him in his car. When others went on teaching trips, he would give at least $20 from his pocket to help cover their petrol expenses.

Leong Tat Chee was also a meticulous planner of teaching activities. He would select the team members and inform them to plan for the trip a few weeks in advance and to apply for leave where necessary, all through letters as not many people had telephones in those days. He had names of the friends and contacts in the areas to be visited. He wrote to those friends letting them know the date and time of the visits, making sure a confirmation was received to ensure the visit was not wasted. Records of friends visited were also kept for future follow up meetings. Leong Tat Chee was not only a great teacher himself, but was always looking out to assist other teachers in the field. Whenever believers went on a teaching trip, he would follow up with a string of letters, giving them encouragement, and send them teaching materials.

Leong Tat Chee went to teach the Faith in various countries. Yankee Leong, the first enlightened soul to accept the Faith in Malaysia and Leong Tat Chee were always interested in spreading the Faith among the Chinese in this as well as other countries. They left for Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan to answer an urgent call for teaching assistance from these places in 1965. They were the first Bahá’ís of Malaysia to go travel-teaching out of their country. Leong Tat Chee made his second teaching trip to Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan in 1968. Leong supported in the translating of Bahá’í books into Chinese for the use in Taiwan and also other Chinese speaking countries in the future. Leong also travelled to New Delhi, India in 1967 to participate in the Inter-Continental Conference, and after this Conference, visited Sri Lanka and travel taught there. He had undertaken teaching trips to South Thailand and Singapore as well. His desire was to go pioneering and get his bones buried, but this was not to happen owing to him falling sick.

Leong Tat Chee was privileged to participate in the election of the first Universal House of Justice in Haifa, and the First Bahá’í World Congress in London. He was one of the nine delegates from the Regional Spiritual Assembly of Southeast Asia and the only Malayan and only ethnic Chinese among the delegates to elect the first Universal House of Justice. At this first international convention, he was also appointed a Teller and was amongst the first of five teams to count the ballots. At the First World Congress held in London, Leong Tat Chee was singularly honoured to be selected to represent the world’s seven hundred million Chinese. When Leong Tat Chee was invited to say a few words, he stood up, greeted the Congress and sketched the progress of the Faith in Malaya. He commented that “… most of the believers in Malaya are between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, and their enthusiasm and steadfastness pushed older people like myself to go forward and do more for the Cause, and they long for the day when they can participate in spreading the Faith throughout China.” Years later, he would often remark what a wonderful occasion that was, to see such a special gathering of mankind coming together as one world family.

Leong Tat Chee is standing to the extreme right at the first Convention of the Regional Spiritual Assembly of South East Asia, Ridván 1957. Seated in the center is Hand of the Cause Mr. Ali Akbar Furutan. Seated at extreme right is Dr. K.M Fozdar, Spiritual Father of Leong Tat Chee. Yankee Leong stands sixth from the left.

L-R: Jamshed Fozdar, Dempsey Morgan and Leong Tat Chee in front of the International Bahá’í Archives Building, Haifa, on the occasion of the First International Convention.

Leong Tat Chee held several responsibilities during the formative days of the Faith in this country. He started his administrative responsibilities as Chairman of the Local Spiritual Assembly of Malacca town in 1955. He was elected on the Regional Spiritual Assembly of South East Asia in 1958 and served on the body till 1963, elected to the first National Spiritual Assembly of Malaysia in 1964, and appointed Auxiliary Board Member in the same year. He was the first believer from West Malaysia to serve as Auxiliary Board Member. He was also a member of various national committees.

Leong Tat Chee gives a report at the first national convention of Malaysia, 1964.

At the extreme left is Phung Woon Khing. At extreme right is Lily Ng, and to her right is Harlan Lang.

Leong Tat Chee was very keen to sacrifice something big as a way of thanking Bahá’u’lláh for having led him into accepting the Faith and he thought of donating his house, his one, and only property, for the Faith. At the National Convention of 1967, Leong Tat Chee stood up and announced that he wanted to donate his home 31, St. Johns Hill Road in Malacca to the National Spiritual Assembly. Before the sound of the applause subsided, Yankee Leong stood up and announced that he too would like to donate his house at 333, Rahang Road, Seremban to the Bahá’í Faith. The spirit of sacrifice that prevailed at this Convention was marvelous. Leong Tat Chee’s house up to this day is still used as the Malacca Bahá’í Centre. In Leong Tat Chee’s honour, the room where he passed away was retained in as original a condition as possible and is used by the Local Spiritual Assembly of Malacca as their meeting room.

A gathering in 1971. His house had a constant flow of visitors and housed numerous Bahá’í activities.

Throughout his life, Leong Tat Chee made sure no one went against the institutions, by word or deed. Whenever anyone spoke against the institutions, he would lovingly counsel them to the right course. He pointed out to them the avenues and recourse available in the Faith for the believers, such as meeting the institutions or writing to them directly. Anything has spoken outside this forum, he said, would be tantamount to backbiting and slander. He was always armed with the appropriate Bahá’í passages.

Leong Tat Chee was a tireless writer of letters. From the early days, he would write inspiring letters and notes to Bahá’ís in various parts of the country. He was especially fond of writing to those in the teaching field. The recipients had reported that these letters came as a balm at a time when their spirit was at the lowest in the teaching field. Many Bahá’ís who had received his letters preserved and treasured them for the love that had gone into writing those letters. Leong Tat Chee had a tremendous capacity for writing letters that would move the hearts of the recipients.

Leong Tat Chee would be so excited every time Bahá’í visitors came to Malacca. The visitors, especially pioneers and visiting Bahá’ís, would share their experiences and knowledge with the local Bahá’ís. Any time these visitors came, Leong Tat Chee, himself would organize their meetings with great excitement. He often informed believers around Malacca state to come for these meetings to listen to their talks and to seek clarifications from them. Leong Tat Chee also made it a point to take the visitors in his car to other parts of Malaya.

The life of Leong Tat Chee was much moved by his association with visiting Bahá’ís especially the Hands of the Cause of God. Leong Tat Chee himself has been fortunate enough to meet several of the Hands of the Cause of God at various meetings, both abroad and within Malaysia. He saw them as generators of inspiration. He knew the special role and rank they occupied in the Faith and had tremendous love, respect, and admiration for them. He showed his utter humility in their presence and gave full attention to their talks. He himself has been reported to have told the younger generation at gatherings that they should look for every opportunity to meet the living Hands of the Cause of God as they belong to an institution that cannot be reappointed or replaced. He moved closely with Dr. Muhajir who had made several trips to Malacca since 1957. As early as 1966, Leong Tat Chee wrote to Dr. Muhajir asking him to decide the future of his service for the cause, as follows, “I have found a way of investing my Provident Fund, if I retire, that can give me a steady income to finance my domestic teaching trips for years… Please advise me whether I should retire from Municipal service and man the fort in Malaysia… My dear beloved Hand of the Cause, if you feel that I should retire and serve Lord Bahá’u’lláh entirely, please advise me to do so”. Dr. Muhajir saw the enthusiasm in Leong Tat Chee and advised him to go ahead and retire early to be able to give full-time service for the Cause.

The early believers of Malacca always said that Leong Tat Chee was a visionary in his thinking. Whenever believers talked about any unpleasant happenings among believers in the community, he would often say, “What you are witnessing now is nothing but dark clouds. The fate of the dark cloud is to move and disappear. What you are seeing now are also like dark clouds which would soon disappear. Bahá’u’lláh has promised a new race of men and a new civilization would be established, and we must believe that whatever has been said by the Prophet would come to pass. We are all in the very beginning stage of building that new civilization. And it is we who have to patiently build that new civilization. We know the future is certainly glorious.”

From the very early days of acceptance of the Faith, Leong Tat Chee strove hard to live by the teachings to the best of his ability. Even at his workplace he was highly respected for his dedication, as he employed the teachings of “Work is Worship; service is Prayer.” For the exemplary services, the Governor of Malacca state awarded him with the Pingat Jasa Kebaktian (Meritorious Service Medal) in 1966.

Leongs meeting with the Governor of Malacca on the occasion of being awarded the Meritorious Service Medal, 1966

Evening of His Life

Towards the later part of 1968, Leong Tat Chee was diagnosed with cancer of the throat and had a surgery done in Malacca town. Gradually cancer slowed down a lot of his physical activities. Yet Leong Tat Chee continued tirelessly to discharge his duties as an Auxiliary Board member through his extensive, loving and regular correspondence with pioneers, assemblies, committees, youth and even isolated believers both within and without Malaysia. In 1969, the Universal House of Justice called upon Malaysia to prepare Singapore for the establishment of its own National Spiritual Assembly in the near future. Leong Tat Chee was suffering from cancer, and yet his desire to fulfill the call of the Supreme Body overcame that pain. Mrs. Leong Tat Chee who saw her husband’s great longing to serve, communicated with the Continental Board Office and informed that she would close up her home in Malacca and leave for Singapore so that Leong Tat Chee could serve there. Yankee Leong, Leong Tat Chee and Mrs. Leong Tat Chee established a teaching base at the Bahá’í Centre in Frankel Estate and involved in teaching activities. But the pain of cancer became quite unbearable for Leong Tat Chee which forced him to return to Malacca for treatment. In Ridvan in 1970, five new Assemblies were elected in Singapore, and in Ridvan 1972, the first National Spiritual Assembly of Singapore. When this news reached the ailing Leong Tat Chee, he expressed his tremendous joy over this achievement.

Yankee Leong and Leong Tat Chee when teaching in Singapore

Yankee Leong and Leong Tat Chee when teaching in Singapore

When Leong Tat Chee was expected to rest upon returning from Singapore trip at the end of 1969, he surprised everyone by appearing at the Seventh National Convention of Malaysia in 1970. Leong Tat Chee was visibly moved by the warm love expressed by the Bahá’ís who had gathered there. Counsellor Dr. Chellie Sundram, paid tribute to Leong Tat Chee in glowing terms. Then Leong Tat Chee paid a tribute to Dr. K.M. Fozdar, the pioneer who had given him the Faith and became his spiritual father. Leong Tat Chee thanked the Malaysian Bahá’ís for their loving prayers said for his own healing. Then he added a word of caution taken from the writings of the Guardian, “If anyone should for a second think or consider his achievements are due to his own capacities, his work is ended and his fall starts. This is the reason why so many competent souls have after wonderful services, suddenly found themselves utterly impotent and perhaps thrown aside by the spirit of the Cause as useless. The criterion is the extent to which we are ready to have the will of God work through us.”

With his health deteriorating further, he still attended the 8th National Bahá’í Convention held in 1971. At this convention, Leong Tat Chee encouraged many believers from the Chinese background to take the Faith to the Chinese population in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau. Leong Tat Chee expressed his wish was to take the Faith to these countries, should his health permit.

His last public appearance was at the Summer School held at the Malacca High School in July 1972. Using some signs, he requested to be brought to the Summer School to be in the company of the Bahá’ís, for the last time. There Leong Tat Chee shook hands with many Bahá’ís and was seen in a cheerful mood. He struggled with great difficulty in trying to converse with some of them, but his words were not clear. After the Summer School, some Bahá’ís went to the house of Leong Tat Chee to bid him good-bye, knowing that they would not see him again.

Although he was suffering from severe pain in the last days, he refused to consume morphine. Instead, he resorted to prayers and invoking the name of Bahá’u’lláh. Feeling his death was imminent, Leong Tat Chee told his wife the evening before he passed away to clean him very well as he was going on a long journey and that she should not worry about him. It was 12:10 a.m. on 10 October 1972, that he breathed his last. His wish was to die with Bahá’í prayers on his lips and true enough, he died this way as Mrs. Leong said she could hear him praying just before he fell on the bed. Beside him was a photograph of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, and a prayer book in which he had a long list of names of those for whom he had been praying.

Leong Tat Chee had a very beautiful Bahá’í funeral. On the afternoon of 12 October, many friends from Malaysia and abroad came to pay their last respects. Those who spoke at the funeral accorded the highest praises for him. The hearse carrying the remains of Leong Tat Chee began its journey with several vehicles and many mourners following the hearse. Police outriders were arranged to control the crowd and traffic going to the burial ground. There were broken hearts all the way to the Bahá’í burial ground in Bukit Baru, Malacca. Leong Tat Chee had a glorious send-off, a funeral fit for a king!

The Supreme Body, on being informed of the passing of Leong Tat Chee sent this message:

DEEPLY GRIEVED NEWS PASSING SINCERE PROMOTER CAUSE LEONG TAT CHEE HIS DEVOTED LABOURS INCLUDING SERVICES AS MEMBER AUXILIARY BOARD WILL LONG BE REMEMBERED STOP HANDS JOIN HOUSE IN CONVEYING RELATlVES FRIENDS LOVING SYMPATHY ASSURANCE FERVENT PRAYERS SHRINES PROGRESS HIS SOUL.

I am one of the grandsons of Leong Tat Chee. He died when I was only very young and my memory of him is very vague. But what I had written are snippets that I had picked from a 336-page book that our renowned Bahá’í historian Mr. Manisegaran Amasi has written on my late grandfather. This book is entitled “Leong Tat Chee – A Sincere Promoter of the Cause”. As I was going through the manuscript to provide a foreword for this book, I came across so much information about my grandfather, some of which, admittedly were hitherto unknown to my family members. It is amazing how Manisegaran could gather so much information and complete this book within three years. The Leong family wishes to thank Manisegaran for his thorough and meticulous research work.

The book is now available

Reading the book, one would gather many facets of Leong Tat Chee. He had certainly left a rich and everlasting legacy. He was truly generous in prosperity and thankful in adversity. He had given financial assistance to several believers, especially students and unemployed and those in utter poverty-mostly unasked and unnoticed. His words were as mild as milk. Many believers who were down in spirit had sought his company as his very company would elevate their spirit. He radiated so much love that could be felt in his presence. Whenever he saw or heard of believers arising to serve, he was always about the first to praise them in person or through letters. He had a list of friends who needed to be cheered up and would visit them frequently. His advice was always from the Writings. From the early days, he developed the habit of waking up at dawn to say his prayers at least an hour, to draw guidance and divine assistance in his daily activities. He often saw all the tests as gifts from God and was thankful for all the sufferings he went through. However violent his tests were, he was never shaken, he kept his Faith in the helping hand of God, and pressed on with his Bahá’i work. He had lamented silently for the severe tests that he faced but learned to resign to the will of God. He never complained of anyone. He was very fair in judgment, though he himself never judgmental. He was very much embodiment of humility in his own way, never seeking prominence over others. Much more could be said of this star servant of the Cause. Today a national teaching institute that was constructed in Malacca in 1965 has been named after Leong Tat Chee, following his death, in his honor.

Manisegaran has gone the extra mile to gather accolades placed on Leong Tat Chee by some early believers who moved closely with him.

Yankee Leong, the first enlightened believer of Malaysia admired the wide reading habit of Leong Tat Chee. Yankee Leong observed, “If there is a Bahá’i matter to be clarified, it is Uncle Leong that Bahá’is go to. Uncle gets the books and reads out aloud the relevant passages in the Writings he knows so well. He never says “I think so.” He always says, “Let us look into the Writings.”

K.S. Somu a believer since 1955 says, “It is a wonder that Bahá’u’lláh has raised a great soul like Leong Tat Chee who has so much impact on my own spiritual growth. I may forget my own biological parents, but simply cannot forget my spiritual father and mother – Mr. and Mrs. Leong Tat Chee…”

Kumara Das, an early believer of Malacca since 1955 says, “He was the first to introduce the healthy habit of home visits to teach and encourage and deepen believers. The spirit of unity was very strong in Malacca. An outstanding person in this scenario who rose to the occasion to consolidate and strengthen the activities of this new-born Faith was none other than Uncle Leong Tat Chee…”

Anthony C. Louis, another early believer of Malacca since 1957 says, “Leong Tat Chee was very much a fatherly figure to the Bahá’is in Malacca and took a keen interest in the spiritual health of each individual he came across. He was also concerned about the financial welfare of those downtrodden. People always looked upon him for any advice and guidance as he always quoted the Writings, seldom would he give his own opinion. Even his personal opinions were very much influenced by the writings….”

The late Counselor Dr. Chellie Sundram had shared, “Uncle Leong Tat Chee is not one who loves the Faith but is one who is in love with the Faith… He was like a devoted gardener who was not satisfied with simply planting the seeds but who carefully tended the young plants and nurtured them into maturity…..many of those believers who are now scattered throughout the country or gone pioneering abroad, were all deepened through Uncle Leong and have themselves become centers of attraction.“

Dr. John Fozdar, a Knight of Bahá’u’lláh residing in Kuching, Sarawak and one who had known Leong Tat Chee since 1954 says, “Leong Tat Chee who accepted the Faith in the early days later became one of the brightest stars in the Malaysian Bahá’í sky. Leong Tat Chee is known to all communities in South East Asia and was one of the shining lights of this distinguished community. …”

Dr. Vasudevan Nair, a believer of Malacca since 1961 and now settled in India recollects, “Leading the remarkable band of the believers who had become Bahá’is in the Ten Year Crusade was Leong Tat Chee who prayed and travelled everywhere… The remarkable thing about him was that he had, after his declaration, completely shed his old attachments to his religious and racial background and with an unmatched zeal taught the Cause of God…

Betty Benson, who had known Leong Tat Chee since 1958 and now living in Guam says, “I consider Mr. Leong my true spiritual father whose deep love for Bahá’u’lláh was exemplified in his life…His commitment to and love for the Faith was so advanced that he used every opportunity to assist each and everyone who found the Faith to become committed and steadfast. In order to nurture a growing community, he made it his duty to visit, remind and offer transportation to those in need… Both my children were born in Malacca and the Leongs were my parents in every way. I could not have wished for more…”

Inyce Gopinath who had known Leong Tat Chee since 1961 says, “Uncle Leong Tat Chee was an imposing personality. His sincerity of belief in Bahá’u’lláh helped me to take that leap from my Church to a total unwavering steadfastness in my devotion to Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation. .….Uncle Leong Tat Chee was the most approachable and warm member among the Malacca Bahá’is then. He nurtured my brother every step of the way. He was a real father-figure, and awesome when he talked about the Faith.”

Bhaskaran Sangaran Nair, a believer in Malacca since 1959 says, “Whenever we went to his house Leong Tat Chee used to say “Hello Brother, Alláh-u-Abhá” and then hug us. He used to copy down notes on the Writings and then post to us. When we visited him with the notes, he would discuss and seek our views on the Writings. He was able to move with people of all ages. Whenever there was a wedding, a few cars would go to give all the support. At the wedding, Leong Tat Chee would give a framed picture of the Marriage Tablet as a present. Whenever he visited Assemblies, he would ask if Bahá’i fund has been established. If the answer is no, Leong Tat Chee would donate some money to initiate the Bahá’i fund. He was a very practical man….”

Theresa Chee, eldest daughter of Yankee Leong says, “In my association with him I have found Uncle Leong Tat Chee to be immersed not only into the Writings but into the Faith altogether. He never had any trace of jealousy or envy in the success of other Bahá’is. On the contrary, he gave all the encouragement. He was very close to my father and they undertook several teaching activities together both in Malaysia and abroad. I saw them as one soul in different bodies. My father used to say many nice things about him. It is most unfortunate that he had not lived long enough for the later generation to appreciate his services and prominent role in the Faith. ”

Lily Ng, another daughter of Yankee Leong has this to say, “Leong Tat Chee and Mrs. Leong, his wife was a couple much loved and much admired by me. I found him to be very courageous and energetic. He was always a joyful person to meet, for his words were inspiring. He would hold my hands and say “Sister, what a wonderful time we are living in – the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh must be widely spread and we are chosen by Bahá’u’lláh to do so.” He was always cheerful, full of words of hope and encouragement…I am yet to come across any believer or non-believer who has demonstrated full submission to the will of God under all circumstances, however difficult they may seem.”

The late Jami Maniam who accepted the Faith in 1957 and to whom Leong Tat Chee was his mentor had said, “His company simply enhanced our spirit. He lived a true Bahá’i life. Each of his movements, each of his words reflected the essence of the Faith. He lived according to whatever he had read in the Writings. In my personal opinion, it was not a coincidence that Leong Tat Chee was born in Malaya. It was providential that certain souls were made Bahá’is to show the way to others. Leong Tat Chee was certainly one of them who showed the way to many to emulate. It is unfortunate that the present generation did not have much opportunity to associate with him. He was saintly in every way.”

Sathasivam Sithambaranathan of Malacca who had moved with Leong Tat Chee since 1965 says, “The Bahá’is rose to great heights to teach the Faith throughout the state of Melaka and Peninsula Malaya. I would say beloved Uncle Leong was a devoted servant of God. He was an untiring travel teacher who had visited nearly every Bahá’i community and even isolated believers in Peninsula Malaya. He had dedicated a part of his life to God, Bahá’u’lláh and mankind.”

Koh Ai Leen, who accepted the Faith in Malacca in 1958 and is now residing in Germany says, “In the early days when we became Bahá’is we all somewhat needed spiritual fathers to nurture us in the Faith. In Malacca, we had some fatherly figures but it was Leong Tat Chee who was a towering figure. He took every effort to care for the new believers and their souls. During moments of distress, he was there as a balm to our wounded hearts. And there had been many moments when I had gone looking for him for advice and strength. During such moments, most of the time guided me through the Writings and his own words of warm encouragement…I wish to say that it is such fatherly figures like Leong Tat Chee who are needed in abundance in the Bahá’i communities.”

K. Krishnan who had undertaken several teaching trips with Leong Tat Chee from 1962 says, “The youths in those days were very attracted to him. We were like iron filings attracted by the magnetic power of his voice. He was fond of welcoming by saying “Brother! Brother!” There are very few people in the world who bring changes in the lives of others. Leong Tat Chee was one of those who was instrumental in changing my life and lives of several others in Malaysia.”

Isaac De’ Cruz who accepted the Faith in Seremban town in 1960 and now settled in the United Kingdom says, “Those days it would be a pleasure just to go all the way to the north, east and south of Peninsula Malaysia driving sometimes for 10 hours, to participate in teaching and deepening efforts. We would make these trips joyously and would hardly feel any ill-effects but looking back I can understand how Uncle Leong must have had to put up with those long journeys while he was in his late age. But I can never recall any negative comments from him. He was always and ever serene and as so often happened, while I would be driving, he would be dishing out all those lovely snippets of deepening materials…”

N.S. S Silan who accepted the Faith in Penang in 1965 and now settled in Australia says, “For the Malaysian Bahá’i community we were further blessed when we had early believers like Uncles Yankee Leong and Leong Tat Chee, both of whom set high standards of obedience, servitude, and humility in their service to the Faith. They gave their time, dedicated all efforts, set such high standards of service, that we all tried our best to follow…On many an occasion, I still reflect on his person and this gives me much needed the inspiration to move on and serve, even to this very day.”

It is very gratifying to read so many moving praises by the early believers on my late grandfather. They only serve to make we family members and generations yet to be born very proud of an illustrious lineage that my grandfather had ushered through his services for the glorious Cause of Bahá’u’lláh.

Here, at long last, my family has gained a deeper and accurate understanding of the life, legacy, and contribution of Leong Tat Chee to the Cause in Malaysia.

The Leong family has decided to donate all the proceeds from the sale of this book to the National Bahá’í Fund, Malaysia.

For more information on how to purchase the book, please contact the Malaysia Bahá’í Publishing Trust at https://www.facebook.com/bptmalaysia/ or email bpt@bahai.org.my or call +603 7981 9850.

Soheil Chinniah and Bernice

Australia

31 December, 2017

Copyright©bahairecollections.com