With the Aborigines of Australia

Dr. Firaydun Mithaq

It was through some turn of unexpected events and certainly by some mysterious forces that I landed myself in serving the Faith among the Aboriginal people in Australia.

The scene of the drama unfolded in the office of the Iranian Consulate General in Seoul, South Korea in 1985. My family and I were pioneers there. I was friendly with the Consulate General in Seoul. My family had to endure the hardships of being rejected of our rights of citizenship because being members of the Bahá’í Faith and were forced to find refuge in another country. “I am an Iranian citizen, and why can’t you help me?” was my question. He replied. “Yes, we are friends, but the government of Iran has given us strict orders not to extend or renew that passports of the Iranian people who profess the Bahá’í Faith. My hands are tight. I am really sorry.” But what can I do, where can I go with the expired passports of my wife, my two small children and myself after living in Korea for nine years? I asked him again if there was any other way. He said, “Only those Bahá’ís who sign a letter of resignation from the Bahá’í Faith and return to Islam can be helped. But in your case, you are not only a Bahá’í, but you have established a Bahá’í Center and propagate your religion here.” He then handed over some newspaper clippings and continued. “Here, see your monthly Bahá’í articles in the Korea Times and the Korea Herald. We can give you a letter with which you can go back to Iran, but that will be at your own risk.” When he said that, I just left the Consulate with a heavy heart. Many other Persian Bahá’ís who lived outside Iran had faced the same fate. But I was confident that with the promise that Baha’u’llah has given that He would not abandon His servants in need of help. That assurance consoled me.

Next I turned to the Korean government and requested for asylum or some arrangements that could keep us in Korea, but it was not granted. We had to leave Korea! We consulted the Universal House of Justice and we were advised to migrate to Australia. The National Spiritual Assembly of Australia sponsored us, and in September 1985 we arrived in Perth. We were sad to leave Korea but were happy to be in Australia. In fact, a new and rare opportunity unfolded in our life.

Upon landing in Australia, we discovered that West Australia was wide open for teaching. It was delightful to see that in Australia one could get higher education with government support regardless of one’s financial status. Hence, we realized that our moving temporarily to Australia was indeed the blessing in disguise as we could get our two daughters educated.

Over one thousand Persian Bahá’ís from Iran had settled in Perth with refugee status during the eighties and the number of the Persians believers had outnumbered the Australian Bahá’ís. We did not want to add to the population. Consulting with the Bahá’í Regional Office of West Australia made us settle in Carnarvon where we could participate in aboriginal and city teaching, and help in the formation of its spiritual assembly. Carnarvon had a population of approximately 5000, half of whom were aboriginal people. Many aboriginal population lived in Mengele village in the outskirts of Carnarvon, while other aboriginal families lived in scattered individual homes in the town.

On 2 June 1985, my family arrived in Carnarvon. While in Laos we had gained some experience in teaching the tribes. Since aboriginal teaching in Australia was new to us, we decided to devote more time to aboriginal teaching in the nearby Mengele village and in other aboriginal communities in the Northwest. Introducing the Bahá’í Faith to the aborigines was a teaching goal in Australia, although it had its own challenges. The historical and cultural barriers resulting primarily from lack of trust and genuine love and fellowship of the urban Australian society towards the aborigines posed major obstacles to their development and education.

It is interesting to note that an Aborigine Committee was established in 1956. Fred Murray of the Minen tribe, and Beryl and Marjory Tripp, became a Bahá’ís in 1961. Fred Murray attended the First Bahá’í World Congress in London in 1963. By 1968 the Bahá’í community included members of the Andilyaugwa (Groote Island), Bunanditj, Jirkia Minning, Junjan, Minen, and Narrogin tribes. By 1983 there were four Local Assemblies in Aboriginal areas. So, we arrived at a time to continue with the good foundation already laid before us. As working with aborigines in Australia was a new experience to us we decided to get prepared. We went through the Writings and came across this highly useful guidance that the beloved Guardian had left for reaching the Aborigine friends:

It is a great mistake to believe that because people are illiterate or live primitive lives, they are lacking in either intelligence or sensibility. On the contrary, they may well look on us with the evils of our civilization, with its moral corruption, its ruinous wars, its hypocrisy and conceit, as people who merit watching with both suspicion and contempt. We should meet them as equals, well-wishers, people who admire and respect their ancient decent, and who feel that they will be interested as we are in a living religion and not in the dead forms of present-day churches.

(Shoghi Effendi, Lights of Guidance, p. 523)

In a letter of 24 July 1955, Shoghi Effendi reminded the National Spiritual Assembly of Australia and New Zealand in these words “…the importance of increasing the representation of the minority races, such as the Aborigines and the Maoris, within the Bahá’í Community. Special effort should be made to contact these people and to teach them; and the Bahá’ís in Australia and New Zealand should consider that every one of them that can be won to the Faith is a precious acquisition.”

Several fundamental questions on teaching among aborigines occupied my mind such as:

- What is it that attracts the aborigines to the Faith?

- How can they understand the significance of the revelation of Baha’u’llah and join the Faith?

- How can they be helped to fall in love with Baha’u’llah and become transformed?

- While many of the aboriginal attributions to human virtues are commendable, how can they be helped to find the way of gradually moving from those obsolete and outdated aboriginal social practices that are not in alignment with the spirit of the Faith and begin assuming the Bahá’í way of life?

- How deep and to what extent the aboriginal believers are accepted by the non-aboriginal Bahá’ís in Australia?

- What are the signs of their spiritual transformation and what would it take to nurture them?

- What would it take to help them become the teachers of their own fellow aborigines?

With these questions in mind we began reflecting and consulting on the complexities that unfolded before us. That made us realize the process of serving and working with the aborigines was more challenging than we had imagined. However, we kept moving forward seeking divine assistance.

Once in a month or so we visited Onslow, gathered the friends, had small devotional meetings and deepening sessions together with aboriginal friends. Since Onslow was about 500 km away, it took half a day to reach the place. Therefore, we could not visit Onslow community as often and as much as we wanted to. It was not an easy task, but we were determined moving forward and tried doing the best we could.

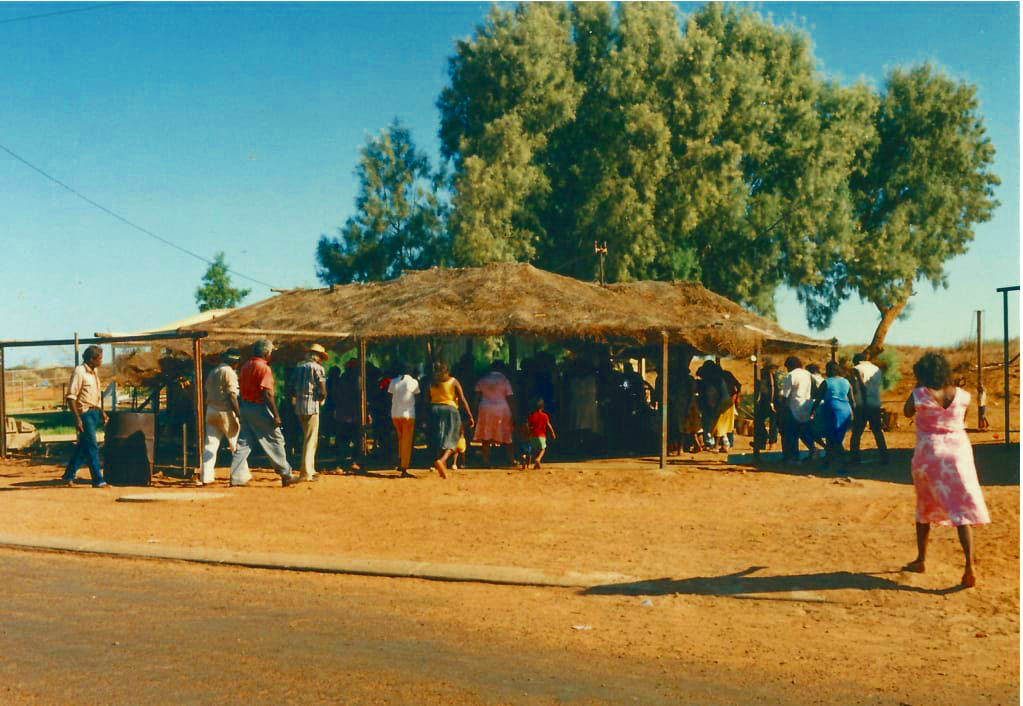

Friends gathering in Onslow for a meeting

My wife Giti quickly established the bonds of friendship with the aboriginal women. From the first week of our arrival in Carnarvon she started working as an Assistant at the Peter Tidman Optometry. With that she easily got acquainted with many people including the aborigines. She soon formed the core group of aboriginal women for strengthening family ties and friendship. Once in a week or a fortnight few aboriginal and other women got together, prayed and socialized. The process of working with women to develop anything concrete was slow, but it continued maintaining friendship and good will.

Giti Mithaq standing with three of the core group women in Carnarvon

One interesting annual event that the aborigines commonly held was the initiation festival and ceremony. Some close Bahá’í friends liked to attend these events as guests and observed their processions. The initiation ceremonies were large cultural gatherings that were usually held for several days in the bushes, or bare ground under shade of the trees. They consisted of body painting, aboriginal singing and dancing, teaching sacred aboriginal laws and ordinances to their youths. The youth were circumcised at the point of their attaining puberty and adolescence. Aborigines from several distant villages and communities would join and celebrate this annual event in the spirit of unity. At these initiation ceremonies, we could meet and befriend many new people. That opened the opportunity of sharing the Message of Baha’u’llah. As our connection with aboriginal friends expanded over the years, the aboriginal teaching in Northwest took new momentum. I have been at two major initiation festivals, in Onslow and in Roe-Bourne. In the Onslow initiation festival, there were a group of Bahá’í teachers and visitors. When we got at the initiation venue we were asked if we wanted to participate in the ceremonies or remain as observers.

Arman Yazdani, a volunteer of the Youth Year of Service in Onslow and I attended the initiation ceremonies for the first time. Arman and I had to remove our shirts like everyone else, paint our bodies and wear the compulsory red hairbands, which we did. Then we joined in one of the rows of the group dancers and danced with them- that was real fun. This dancing and singing procession continued for over two hours under the hot sun until nearly everyone was out of breath, collapsed and fell on the ground. At sunset, all went back to their camping spots, and Arman and I went to our tent. The girls stayed inside the tents while the males slept outside and around the tents.

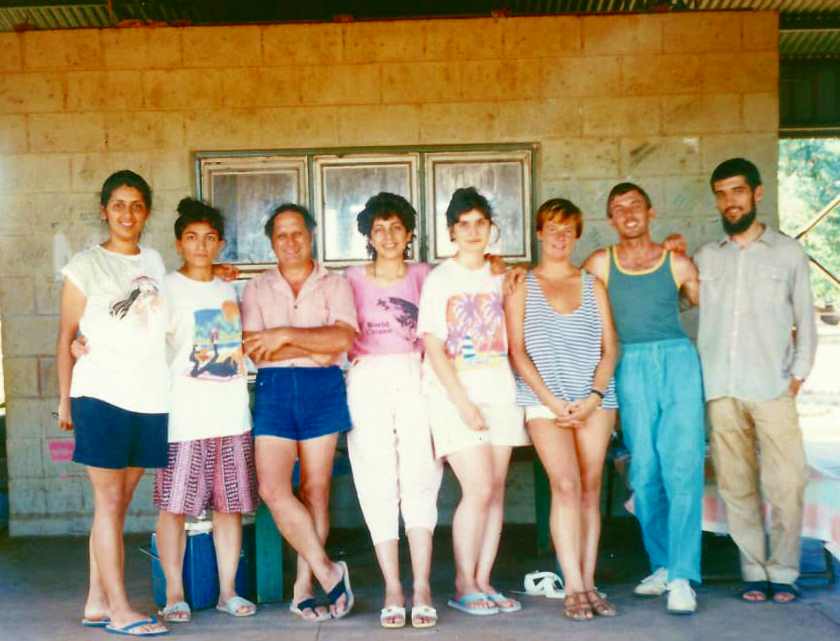

Youth Year of Service volunteers with traveling teachers in Broome. R to L: Ezaz Kowsari, Lloyd Brown, Kate Alai and Fereshteh Kashani. Firaydun Mithaq is third from left.

After dinner, the night activity began, consisting of only women singing aboriginal songs and dancing while others sat around the glowing flames of fire and watched. At this time, the elders took the adolescent boys to a secret spot in the bush for teaching them the sacred aboriginal laws and tales, and performed circumcising. At dawn, they returned to the camp and joined the congregation of dancers. Each night a new batch of young boys was taken to the secret spot for the same purpose. This continued for several days and nights until all the boys were taught the laws and were circumcised. Then was the adoption ceremonies of pairing small children, boys and girls, for future union in possible marriages. Then was the adopting ceremony for grown up men as sons and women as daughters into new families. At first, Arman and I wanted to be adopted as sons to aboriginal families but later we learned that some of adoption practices pertaining to close intimacy with women was not compliant with the Bahá’í way of life. Therefore, we declined. We had to know where to draw the line.

Each day they slaughtered a cow to feed over one hundred participants in the initiation ceremonies. They distributed the meat to each family for cooking. We enjoyed being there with them sharing friendship. Our photographer Ivan took some pictures of us dancing with the aboriginal friends during the day-processions. Taking pictures was permissible at daytime but not at night especially with flash lights on. Therefore, she was asked to take the film out of the camera and surrender it to them which we politely did. We lost all the pictures.

It was indeed a great and rich experience to be part and parcel of their way of life. This was one experience I did not have elsewhere, nor do I expect to have it anywhere else. I was happy to be part of their culture.

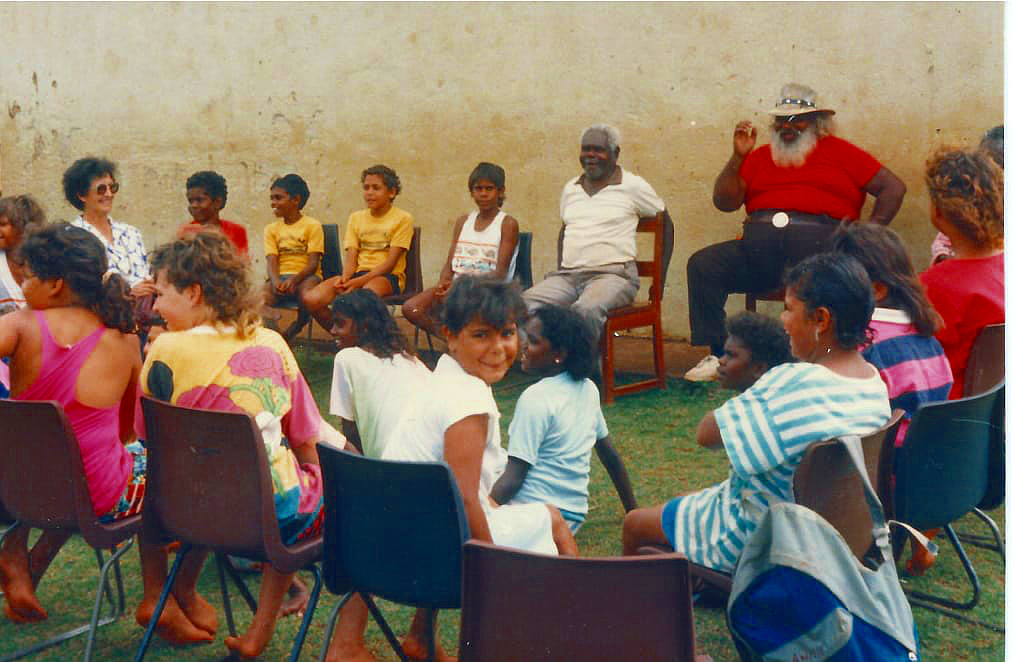

Some distinguished Aboriginal Teachers of the Faith in the eighties

I wish to now share stories of some of the distinguished aboriginal teachers of the Faith

Judy July: Among the aborigines that we met and befriended was Judy July, a woman in her fifties and lived in Onslow. Judy was a pure soul. Her two-bedroom house was like a Bahá’í Center. She devoted one bedroom for the guests who were mostly the Bahá’í travel teachers, while her living-room was dedicated to Bahá’í gatherings. Although poor, she served and fed her guests. Arman Yazdani from Perth was the first youth in Onslow who was engaged in the Youth Year of Service. He stayed at Judy’s house for many months as her guest while he conducted children and youth classes. Several times Judy participated in teaching and consolidation trips to all the communities in Northwest in my company. She served the Faith with zeal until her last breath before she passed away in 1999. She was indeed a remarkable aboriginal maidservant of the Cause of God.

Donny Lewis: Donny Lewis, a nice person with a big body and a kind heart. Donny Lewis accepted the Faith first and then his daughter Rose declared spontaneously. Donny Lewis stopped drinking and gambling- a habit that was commonly prevalent among the aborigines. He fully believed that Baha’u’llah was the Messenger for the day and understood the teachings that drinking was harmful and forbidden. It was not easy for him to be with his friends who consumed alcoholic drinks. At some point, he chose not to be with them, to avoid temptation to go back to old habits. He often joined me on home visits and occasional teaching trips. Below is the story of two of those trips.

The first was the trip that Donny and I made to Cane River, situated 75 kilometers from Naniuntarra Rest House to meet some aborigines from Peedamulla sheep-station who live in the bush. Since it was far off we had to camp there. After arriving at Cane River, we joined the few older men who were sitting on a broken log under the shade of a tree at the high afternoon sun, and started conversing with them. Donny introduced the purpose of our and explained that we were meeting people for promoting love and unity. “To promote unity among the whites or the aborigines?”, they asked. We said we came to unite aborigines, whites and all races. They asked, “How can you do that? White people do not like the aborigines”. I said, “But we like you because we are Bahá’í and believe in unity and brotherhood.” We said no more at that first meeting. We bade good bye and moved to the house of Josh, Donny’s old friend. We sat around the glowing flame of the fire and engaged in conversation while the damper and the kangaroo tail were being cooked. Damper is an aboriginal style of bread baked under the hot ashes of the fire while the kangaroo tail is roasted on hot stones under the ashes of burning fire. At night, we spread our sleeping bags and watched the stars while we continued talking about the Faith. Next morning Donny’s friend Josh declared. Since Josh could read, we promised to bring him some Bahá’í literature on our next visit.

Danny Lewis, in red shirt, teaching the children in Tableland

The second was Donny Lewis and visiting the aboriginal friends in Cairns and Tableland for teaching and consolidation. The trip tuned out to be fruitful and full of fun. Donny shared stories about his teaching activities in the Northwest. Donny was a good speaker, a guitar player and singer. Therefore, during the three-week tour in the Northeast where mostly aborigines resided he taught the Faith, encouraged the friends and entertained people with joy and laughter. The National Spiritual Assembly commended Donny for his devoted services. Donny passed away in 1999. He left a memorable legacy in the history of aboriginal teaching in Western Australia.

Jack Malardy: Jack Malardy, leader of the Karradjarrie people at La Grange, also became a Bahá’í, together with more than one hundred of his people. His village Bidiadanga is located about 3000 km north from Perth, and close to Broome. Catholicism had its root in Bidiadanga, with a church of nearly two hundred aboriginal members turning up for its congregation service. In addition to this there is a large number of people in Bidiadanga that believe and follow the aboriginal traditional religion that is a mixture of belief in cosmology, respect for the land, for nature and the laws that governs. In Bidiadanga a few families had declared and some aborigines warned us to leave the aborigines alone and stop converting them to the Bahá’í Faith. Opposition kept mounting. Scenes of violence among the aborigines was not uncommon, especially when they came under the influence of alcohol. Violence often ended with someone getting injured or killed. Marjorie Tidman, an active and devoted friend was once violently attacked by an aborigine and was stabbed eight times in Carnarvon at her own house.

Jack Malardy standing third from right at a meeting with some believers in Cairns

Life among the aboriginal people could be simply dangerous! One night I was lying down in my car that I had parked under the tree in the backyard of Jack Malardy’s house in Bidiadanga. I heard someone shouting in anger and calling me to come out. As I piped from inside the car I saw a familiar face with a knife in his hand. Perhaps he was drunk or someone had instigated him to hurt me. At that point I didn’t know the cause of that hostility. I thought I should remain in the car and say prayers for accepting the Will of God. After a while as the angry man failed to find me he left and slowly I went to sleep.

At times, it would take a long time to win over the hearts of the friends. One morning while I was still asleep in my small tent in the backyard of Jack Malardy’s house. I was woken by the noise of someone tapping at my tent and asking me to come out to talk. I went out and saw a familiar face of an aboriginal man whose name I don’t remember. On several occasions in the past he had showed dislike toward me, but I had always responded with soft words and praised the good work that he was doing at the Bidiadanga’s experimental plantation. We started off with exchanging the words of greetings. Then he spoke out, “I am sorry that I have been harsh and unfriendly to you but after some time that I have been observing you and examining the things that you have been saying to my aboriginal brothers I feel ashamed of myself. I realize that I have been unjustly hurting a good man. Please forgive me. Also give a book about the Baha’i Faith to read.” I consoled him saying that he had not hurt me at all, and that it was natural to have different views and beliefs about life. He left with a happy face and I praised God for changing hostility to friendship.

Lenny Hopigo: Lenny Hopigo is one of the Jack Malardy’s grandsons. Lenny developed an affinity with Bahá’ís and usually came to see me each time that I visited Bidiadanga, and accompanied me on home visits. He became enthusiastic in the promotion of the Cause in a relatively hostile environment. He was elected as a delegate to the National Convention, representing the Northwest and went to Sydney together with Peter Tidman who was also a delegate.

John Hopigo: John Hopigo is the younger brother of Lenny Hopigo. John worked as Administrative Assistant at the Bidiadanga Community Office. John was very kind and considerate and looked after the people in the village and made their lives easier. John liked playing football with youth in the village and they liked him as well. John did not smoke neither drank any alcohol. He often admonished the youth not to smoke or drink or fight. John, together with his brother helped the youths to organize a musical band that played at various village functions and entertained the people. John was indeed a good manager and kept thing together. I enjoyed his company immensely.

In Ridvan 1985 when I was going to Sydney as a delegate to attend the National Convention, Jack Malardy came along as an observer. He had translated a prayer in his own aboriginal dialect. At the Convention Jack got permission and recited the prayer and spoke briefly about the importance of the Bahá’í teachings and hoped that it would reach all the aborigines in Northwest.

Firaydun Mithaq and Jack Malardy with a few of the Northeast aboriginal delegates at the National Convention

In Brisbane, Alice Spring, Darwin and the Tableland that we visited, he met the aboriginal Bahá’ís and their friends, shared with them his experiences. In Alice Spring friends arranged for Jack Malardy to meet the local aboriginal leader. Jack Malardy conveyed the Bahá’í Message to that aboriginal and shared his experience. The Aboriginal leader was happy about hearing the Bahá’í Message and said he hoped someday unity and justice will prevail in every land.

Roy Wiggins: Roy Wiggins was another well respected aboriginal leader in Broome, some 2,800 kilometre north of Perth, that attracted many tourists and visitors because of its exotic beaches, beautiful sea and the pearling industry. I visited Broome about eight or nine times per year and stayed at Roy’s place and received warm hospitality. Roy was an energetic person and skilful fisherman as well. I had seen him many times he would single headedly catch a five hundred pound dugong from his boat and bring it to shore for his extended family and friends to eat. He sang aboriginal and traditional songs with joy and enthusiasm. He often spoke highly of the teachings of the Faith to others to the extent that they thought he was a deepened Bahá’í. Roy liked chanting aboriginal poems and songs. I had a video camera donated by a friend in the Northeast and I recorded him singing on a cliff at the time of sunset. That was soul stirring.

Once Roy invited us to visit his home village in order to participate in their aboriginal annual festival. At his event I began chanting a prayer in English for unity in loud voice that could presumably reach the heaven. They liked the Words of God in the prayer and commented positively. On another visit when we stayed at the village we were given a chance to talk to a group of senior aboriginal audience about the Faith. We closed the talk with a short prayer. Roy explained that the purpose of the prayer was to beseech assistance from heaven for the well being of the people of his village. After each of us were given a handmade souvenir as a gesture of their love and appreciation we bade goodbye and started to leave. When we were leaving a crowd of people walked with us and saw us off with joy and laughter. Roy always encouraged his aboriginal contacts to learn the lessons of peaceful living from the teachings of the Faith, but never did I hear him to say that he was a Bahá’í. To me he was a Baha’i in heart.

Roy Wiggins seated at extreme left with five members of the Assembly of Broome. Kate Alai is seated at extreme right. Visitors standing at back row R-L: Firaydun Mithaq, Sahba Mithaq, Violet, Fereshteh Kashani, Mania Yazdani and Ezaz Kowsari.

Now that the new believers had reached to some degree of maturity we thought it was time to hold some conferences to familiarize them with the wider circle of unity. Three small teaching conferences were held from 1985 to 1988 – one each in Onslow, Bidiadanga and Carnarvon. The conference in Carnarvon called “One Mob Conference” was attended by about one hundred believers that came from near and far was the most successful one of the three. This conference was instrumental in reaching out to other aboriginal communities such as the Yandiyara located at about 100 kilometers outside Port-Hedland, Tom Price and Derby.

Firaydun is talking to friends assembled at the “One Mob Conference” in Carnarvon

The conference in Onslow was much smaller where about thirty believers from Onslow and from outside took part. The conference in Bidyadanga was attended by about twenty five believers.

Conference in Bidiadanga: Standing R to L: Jack Malardy, Betty Benson, Kate Alai, Danny Lewis, Rose Malardy, Susan, Tachi and Judy July (on chair) Siting on the grass L-R: Ben, Arman Yazdani and Auxiliary Board Member Minoo Fozdar.

We were happy about our monthly visits to the new aboriginal believers and they were glad to see us each in each visit. We prayed with them and, we felt something was missing because helping the aborigines to understand and practice the Bahá’í life was a big challenge and a very slow process. We needed something more than just making visits. The practical solution was initiating “The Youth Year of Service” that had been set on motion by the Universal House of Justice. Therefore, each time we visited Perth this subject was our priority to discuss with youths and their parents and encouraging them to arise and respond to this need. Fortunately, eight devoted youths from Perth rose and responded to the call of the Universal House of Justice. Each time that we visited the youth in their pioneering posts we learnt that the Youth Year of Service was the most effective contribution for the development of the Faith in Northwest. In addition to that was the mobilization of short term youth service from Perth that enabled the youths to participate in periodical teaching activities during school breaks. On each school break that we went to Perth our teaching van was filled with a group of university students that came to the Northwest for periods of about two to four weeks’ consolidation activities. They visited several aboriginal Bahá’í communities, helping them to conducting devotionals, basic deepening and Feast attendance.

Traveling teachers traveling to the Northwest with the Youth Year of Service volunteers. Standing tallest in the extreme back are Arman Yazdani and Lloyd Brown. Fereshteh Kashani is standing third from the left.

There were many lessons we learnt in teaching the Faith to these simple people. We always tried to understand the aboriginal belief system to find the link between the aboriginal and the modern religions. We found the aboriginal religion is complicated and difficult to explain. The aboriginal beliefs and cultural practices may differ in some respects from region to region and from tribe to tribe. Aborigines appear to believe in the existence of a Great Spiritual Being – that is the Creator of the earth, animals, plants and the nature that is manifested by dreaming. At first the aborigines considered the Bahá’í teachers and pioneers no different than another bunch of white invaders at whose hand they had suffered two centuries. Gradually, they saw in Bahá’í teachers’ sincerity, love and unity they welcomed their bounds of friendship. However, as the aborigines came closer to the Faith and Bahá’í visitors, opposition started. Opposition always came first from the churches and missionaries and next by some unfriendly aborigines themselves. But we managed all opposition through prayers and wisdom.

While in Australia the friends in Korea kept on pressing us to come back. We liked that idea but we weren’t sure if it was the right thing to do, since at that time we were deeply involved in the aboriginal teaching and there was a lot to be done. We wrote to the World Centre for guidance, and the Universal House of Justice encouraged our moving back to Korea since the need in Korea was urgent. However the House of Justice left the decision to us as to whether stay in the Northwest or to return to Korea. After living three and half years in Australia we moved back to Korea in August 1989, and settled in Jeon-Ju city located in about 300 km south of Seoul. This time we had to remain in Korea for seven years before moving to our next pioneering location to respond to a teaching goal in China that lasted seventeen years till January 2014. For some reasons beyond our control we were sent out of Korea and are now back to the same country.

I thank Baha’u’llah for sending me out of Korea into Australia. Experiencing numerous incidents of disappointment in the past taught me that whatever happened in the path of service always had a good wisdom behind it. We may not be able to understand them in the immediate effect, but it was always time that revealed the wisdom. The Almighty ordains the best for His servants, though at first it may be practically hard to bear. Had I not been sent out of Korea, I would not have got this rare exposure and experience. I can only recall what the Master said:

… we must realize that everything which happens is due to some wisdom and that nothing happens without a reason. -Promulgation of Universal Peace

During my stay in Australia I gained a new experience altogether. When Baha’u’llah revealed His Revelation it was for the entire mankind. Each ethnic group on this planet had the capacity to accept the Faith. My association with the aboriginal friends in Australia brought me rich lessons. They were able to grasp the teachings of Baha’u’llah very fast and once they had understood the Message they displayed such steadfastness that was truly unbelievable. They were willing to cut off age long habits and customs. When they accepted the Faith they were not only sincere but serious as well. And we Bahá’ís were equally sincere in showing our love for those pure in heart. I saw them as very pure souls yet to be contaminated by the materialism that has already eaten deep into the hearts of urban populations.

Currently we live in Chiang Mai in Thailand, recalling those golden days with immense gratitude to Baha’u’llah.

Dr. Firaydun Mithaq

Chieng Mai

Thailand

30 September, 2017

Copyright©bahairecollections.com

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Dr. Firaydun Mithaq (Mithaqiyan) was 20 years old when he pioneered to Laos in 1962, thus catching up with the last year of the Ten Year Crusade-Plan. Coming from the fifth generation of Baha’is on his father’s side and fourth generation from mother’s side, he was raised in a devoted family. From the age of two to fifteen, he grew up in home-pioneering locations among the Kurd populations with his four siblings. He spent the first seven years of pioneering among the tribal masses of spirit worshipers in the hills, mountains and the urban and rural Buddhists communities in Laos. Mithaq witnessed mass teaching in these areas in 1963, from a single village of forty-five tribal people to about one hundred thousand believers in 1973. In 1973 he was appointed to serve on the Continental Board of Counsellors in South East Asia. From 1975 to 2017 he and his family pioneered to Hong Kong, South Korea, China and Thailand. From 1987to 1992 he lived in the aboriginal communities in Northwest Australia such as Carnarvon, Onslow, Karatha, Roburn, Port headland, Brume and Derby and engaged in travel teaching and community building activities. He currently lives with his wife Giti in Thailand. His pioneering life was highly inspired under the direct love and guidance of the Hand of the Cause of God Dr. Rahamatullah Muhajir.