ON BECOMING AND REMAINING A BAHA’I

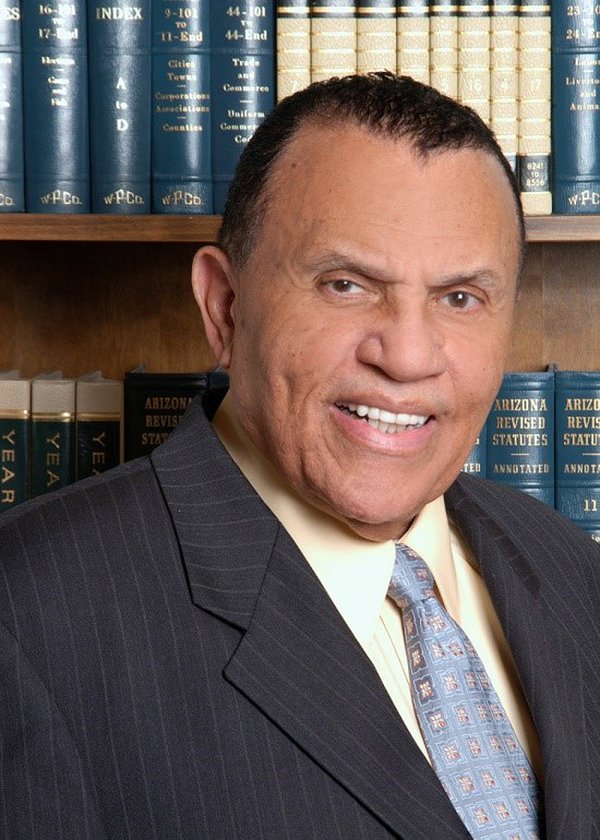

Professor William Maxwell, Ed.D.

PROLOGUE

Imagine the effect on a Baháʼí of meeting nearly all of the living Hands of the Cause of God in his first eleven years as a Baháʼí.

Two of most humans’ most painful life experiences are being born and being born again. Why are both so painful in most cases? This is a mystery operating at many levels of human societies. The question is insistent because almost everyone I know has been painfully disappointed in that their family members were not able to embrace the Baháʼí Faith. They are all created in the image of God and therefore should be able to recognize God’s Messages. Most do not. Indeed, two of the most distinguished Hands of the Cause, Agnes Alexander and Amatu’l-Bahá Rúhíyyih Khánum, over many years and over many encounters shared with me their great disappointments at the rejection of the Baháʼí Message by their dear ones. While Rúhíyyih Khanum’s parents were Baháʼís, it was her relatives who would not come into the Baháʼí fold.

The inabilities by those relatives and ours to “see” and “hear” God’s Truths also applies to a distracted world. Upon becoming Baháʼí, almost all of us feel a spiritual urge to share this Message with everyone in our environment, only to be rebuffed time and time again, until we almost give up, partly blaming ourselves for the failure of our message to get through. This I believe is a misreading of the situation.

Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, the Báb, and Bahá’u’lláh in the Abrahamic family of religions came with ample proof. In the Aryan Family of Religions, Krishna, Zoroaster, and Buddha also offered to their fellow citizens evidence that their missions were divinely guided. Still, only a few accepted. Then, many of those who had accepted allowed themselves to forget their spiritual connections and fell into warring tribes and nations. So the question remains – why does humanity almost universally reject our Saviors?

As everyone knows, most childbirths are painful. But many childbirths in Micronesia are almost painless. In Micronesia, when a woman senses that her baby is ready to be born, she walks down to a lagoon or ocean beach, into the water and waits a few minutes, squats, and grunts once without a single scream. Gravity, with the help of the mother and the baby pushing, pulls the baby out of the birth canal into the mother’s waiting hands. The baby also does not scream much, if at all.

Later in life, I learned that a few spiritual births also are not painful. I realized this in Malaysia. In 1958, about ten Baháʼís, including the distinguished Hand of the Cause Agnes Alexander, were sitting around a dinner table after the first Baháʼí wedding in Malacca town in Malaya, when someone asked everyone “How did you become a Baháʼí?” I was surprised that all or nearly all of them had become a Baháʼí via dreams or other very spiritual experiences. Elsewhere, leaving one’s Mother Faith and accepting a new Faith is almost invariably painful and often equivalent to suicide.

A spiritual rebirth may also be quite painless and “natural” as told dozens of times about the birthing seasons of Christianity and the Baháʼí Faith. For example, when Jesus invited Peter and Simon to join Him in “fishing” for humans instead of fish, Peter and Simon instantly agreed. No strain, no pain.

Now, again the people of the world have been invited into a new belief system defined by Bahá’u’lláh. Why do we almost universally reject such logical truths and then punish anyone brave enough to embrace such doctrines? Allow me then, to relate how I was spiritually born into this religion, without any pain on April 26, 1952.

EARLY INTIMATION

My slow conversion began in 1938 when I was nine years old. Christ had given a wonderful set of teachings for mankind and I had no doubt of that. It was the hypocrisy I saw within Christianity that forced me to separate myself from the Christian culture and also from the African American culture, which decried racial discrimination but accepted many of the man-made ideas and practices of the Christian culture. That psychological separation was a gradual and often painful process. I was looking for spiritual guidance that would create a tranquil heart within me. While my parents were nominally members of the Methodist Church, they were neither very devout nor pious. But I, like most young children, was. One summer Sunday in the DeQueen (Black) Methodist Church, in southwest Arkansas, USA, the pastor suddenly announced that it was time for some baptisms. So he invited those ready for baptism to walk with him to the Cossatot River, about a mile south of the church on the highway toward Horatio, Arkansas. I, along with about 30 others joined the procession to the river. Without thinking ahead, we, one by one, stepped into the river for a “full submersion” baptism by the pastor. When I stepped out of the very cold water shivering in only my shorts, my parents were not there, I had no towel, but some lady I did not know toweled me off and I felt a wave of warmth and joy. My parents were home having one of their usual Sunday lunch parties with relatives and friends. I learned there and then that I had to independently find my own way in life. My parents would not be my spiritual guides in life.

The first intimation came a few Sundays later. The Superintendent of the Sunday School, an almost saintly-in-character lady, said to me, “Junior, I have a lot of books to carry home, would you help carry them?” I was delighted to do so. As we neared the river where I had been baptized a few Sundays earlier, our conversation turned serious and she said to me, “Junior, do you know where Jesus was born?” “In a manger,” I replied, eager to demonstrate that I paid attention to our Bible lessons. “Yes,” she said and then added, “And when He returns?” Somehow I knew it would be different, a surprise, but I did not answer. She answered her own question with such assurance that I suspected that her answer came directly from God, “In a palace.” “In a palace” as an idea, planted itself into my soul, never to be forgotten.

THE SECOND INTIMATION

In 1944, Nancy Phillips, a wonderful Baháʼí teacher living in Phoenix, Arizona, had become friends with the principal of the only segregated high school west of Texas, then named the Phoenix Colored High School, later named George Washington Carver High School. Mrs. Phillips asked the principal, Mr. Lee if his school would like a guest speaker about Persian history at his school. Mr. Lee readily agreed. On stage was this elegant speaker, Marzieh Gail, whose looks and dress alone could hold the attention of high school students for an hour. Marzieh Gail had more than looks and style, however. She had learned as a Phi Beta Kappa scholar at Stanford University and a sweet, exquisitely modulated feminine voice from heaven. She spoke for the usual forty-five minutes about the achievements of the glorious ancient Persian Empire to the entire student body. But not being able to discuss religion, she paused to end her talk with a provocative question, “Have you ever wondered what would happen if Jesus Christ returned to the earth?” That was exactly how her talk ended. There was an overtone of tragedy in her voice that went deep into my unconscious mind there to incubate for four years.

In 1948, I enrolled as the first-ever Black male student at Oregon State University in Corvallis along with a pharmacy student from Oakland, California, Jim McMillan, who was also Black. Interestingly, up to 1948, if a black applied to Oregon State he or she was referred to the University of Oregon at Eugene. Here was I an instant celebrity as the first of two black students at what had been a segregated college for Whites only. One day that fall, in that racist climate, as I was walking across campus, an older student, Frederick Laws, stopped me to introduce himself. Fred, himself a white and an astonishingly mild-mannered person, was wearing a lapel pin. I asked him what it meant. “It’s a Baháʼí pin,” he said. That was the first time that I had ever heard the word. It meant absolutely nothing to me.

The next time I saw Fred, he invited me to their small trailer home near the campus for a “fireside” on the Baháʼí Faith. Fred and his wife, Beth, introduced me to this new Faith, which was different, I thought, but similar to other religions I knew about. He and Beth gave me a small pamphlet by Marzieh Gail to read on my back to my lodging, Campus Club. I was walking and reading the pamphlet at the same time. Here was the headline thought that hit me about 50 yards from their home. “What would happen if Jesus Christ returned to earth?” I recognized that thought, turned around, and asked the Laws, “Is this the lady who lectured in my high school about four years ago?” Of course, they could not answer. But I put two and two together, studied Mrs. Gail’s pamphlet, and found it consistent with my world view. My suspicion had begun to grow that only a new religion can cure our species of the ills that had enveloped mankind. That was the time when I felt all of the other religions had abandoned or lost their divinely endowed status and power, their license, their authority, their legitimacy. I was not yet a Baháʼí, but about half-way there. My suspicion had begun to grow that only a new religion can suffice. The older ones are too corrupt, too embedded in the current degenerate civilizations. Thus, I was prepared to listen to proposals for a better world from a new religion. I was in no way wedded to any of the older religions.

MY THIRD BIRTH

My first birth was very natural with a mid-wife. I was “born again” as a devout nine-year-old boy by a full-submersion baptism in the Cossatot River in DeQueen, Arkansas, by the Methodist Church. Entering the Baháʼí Faith was my third birth.

It was the year 1952 and Frederick Laws was getting ready to graduate, as was I. He and his wife had been pioneering for the Baháʼí Faith to Corvallis for four years as a part of the Second Seven-Year Plan with the goal to establish a Local Spiritual Assembly. There were just four Baháʼís in Corvallis. Fred was desperate to win a victory after four years of pioneering at great sacrifice and a bit despondent and in desperation. Overcoming his natural shyness, Fred said to me, “Bill, we want to form a Baháʼí Assembly here. We need five more members. Will you help us by joining?” I was in the midst of final exams for my degree and knew almost nothing of this religion. But I said yes as a favor, not as an act of faith. Fred explained that the Baháʼí Teaching Committee of Oregon would ask me some questions and offered me several Baháʼí books to study in preparation for enrollment into the Baháʼí Faith. So, I cursorily speed-read them between classes and exam study sessions.

Fred and his wife Beth drove us over to Salem, Oregon, on April 26, 1952, where the Baháʼí Teaching Committee of Oregon would examine and enroll me. Charles Bishop, the white-haired distinguished-looking chairman, asked some easy questions which I must have passed and then gave me a declaration card to sign. I signed it without any sense of the significance of the event. Then suddenly some kind of a wave passed over me and I wanted to hug somebody. So I hugged Mr. Bishop, the first time I had ever hugged a man outside my family. Then, out of the blue, out of any context, he said to me, “This means that you must give up alcohol.” “What have you gotten yourself into?” I asked myself, stunned that there were laws in this new religion that I knew nothing about. Continuing the assault on my naivete, another member of the Committee said to me, “Bill, you will have many tests in this new religion, the hardest tests may come from Baháʼís.”

I have no memory of our drive back to Corvallis, that night of 26 April 1952. Somewhere on that dark night, I think I said to myself. “Okay, I can give up alcohol,” because in my painful memories there were images of my father and uncles spoiling many large family gatherings by going outside to convene around a tree or a wagon to share “a half-pint”, separating themselves from the elders, the women, and children. Then, I recalled that my mother and one of her sisters getting embarrassingly drunk on other lonely occasions. While I had enjoyed wine and beer, I did not see alcohol as a necessity of life. In fact, something inside reminded me that alcohol does much more damage than good. So that minor obstacle faded away.

Acceptance of this new Faith is not without tests, misunderstandings, and opposition for most and extremely difficult for many. In 1958, when seated at a dinner table after the first Baháʼí wedding in Malacca town in Malaya a young Hindu lady quoted her mother, “Why are you spitting in the face of your mother religion?

After you became a Baháʼí, didn’t you often feel that you were being disloyal to your original Divine Guide?” That question often needs a serious explanation. In those instances, many teachers I knew would seize the opportunity to expound on the subject of Progressive Revelation, which was conveyed to the world for the first time by Bahá’u’lláh, the Prophet Founder of the Baháʼí Faith.

THE FIRST TEST

At Oregon State, I passed all my exams and was awaiting my commission as an Ensign in the U.S. Navy. In 1948, one other Black student, at the University of Washington, and I were the first two admitted to the Navy’s NROTC program. As the 1952 June graduation approached, the other 49 midshipmen in my class began receiving notice of their commission and first ship assignments. By graduation day all had received their assignments, except me, the one Black. Finally about ten days after graduation I got a call from the NROTC office on campus to report there and to bring my Navy ID card. I walked into the apparently empty and eerily quiet NROTC headquarters office. Finally, an enlisted man came out of his office, asked for my Navy ID card. He held it up a few inches from my face, tore it in half while starring aggressively at me. I asked no questions and walked out of the Navy forever, though I had trained for four years to be a Naval officer. Thus, I had no plans for the future. I could not even think of using my education degree since I could not qualify for a teacher’s license as Oregon State had decided that being Black, I was not qualified to student teach anywhere in Benton County, Oregon. I was now utterly alone, with no credentials, no money, no future.

WAS I TRAPPED?

There was no one in the University administration that I could turn to. Confused and bewildered, I simply turned to my spiritual father, Fred Laws, and asked his advice. Fred said that he, Beth, and another believer, an elderly lady, were driving to the West Coast Baháʼí Summer School in Geyserville, California, and I would be welcomed to come along for a week, and there I might find some leads for a future job. I gladly consented.

I was assigned to a dormitory with several others including an 18-year-old second-generation Baháʼí, Stephen Powell, who immediately introduced me to Nabil’s Dawn-Breakers. The next day, Sunday, the summer school opened with great excitement. A “Hand of the Cause of God” was to be the speaker and over a thousand people expected that “Unity Feast” under the Great Tree. One could feel the excitement, although I had no idea what a “Hand of the Cause” was. I forgot my troubles and paid attention to the gathering crowd. Old friends embraced with great joy and lots of laughter.

After the Unity Feast, we gathered in the meeting hall with the crowd overflowing to the outside and the MC introduced a very petit, grey-haired, older lady, with no make-up, very simply dressed, as “Mrs. Millie Collins, Hand of the Cause of God.” I remember not a word of what she said, but I do remember that she said she was bringing the love of Shoghi Effendi from Haifa, Israel, to us. Her humility and her evident extreme adoration of Shoghi Effendi were convincing of her legitimacy. She was the first Hand of the Cause I met.

The next morning classes began. The speaker was a Persian young man, Rassekh, I think was his name, and the topic was “The World Order of Baháʼu’lláh.” Soon after opening, the speaker referred to the head of the Faith, Shoghi Effendi, as being “infallible.” All sorts of yellow alarm bells immediately went off in my brain. I was not well educated in world history, but I had some idea of the evil that comes from doctrines such as “The king can do no wrong,” “The Divine Right of Kings,” “The Pope is infallible,” etc.

I left that class after about ten minutes, disappeared up the hill from the classrooms to a quiet isolated grove of trees that bordered the school, sat down, and pondered, “What have I gotten myself into?” Here is Shoghi Effendi, said to be infallible. I felt trapped and totally bewildered and did not feel comfortable disclosing my extreme disquiet to anyone. There I sat alone, in silence, spiritually lost. I did not pray. Although I had signed the card, I thought I was not yet a full-fledged Baháʼí in my heart. For a long time, I sat, missing all the other classes that morning. After a while, the fragrance of pine breezed by my face with a silent appeal, “Be patient, do nothing. Listen.”

I joined in the afternoon classes which were interesting. The friendliness of the people was comforting. One graduate music student at the University of California, Berkeley, Charles Duncan, knowing of my unemployed status suggested that there was a Baháʼí-owned boarding house close to the campus of UC Berkeley and that I might seek lodging there and look for a job in Berkeley. Berkeley was one of the oldest and most stable Baháʼí communities in America. Their Feasts were more spiritual and uplifting than any religious service I had ever attended. I enrolled at the University for a Master’s in Economics and had a spiritual dream. I actually dreamed of meeting Baháʼu’lláh in one of His mansions. His face was radiant and glorious, although He said absolutely nothing to me. His presence alone was like a preview of paradise. A Berkeley professor, Robert Gulick, was married to an Egyptian lady whose mother was Kurdish. So I called them and asked if I could come over to ask Professor Gulick’s mother-in-law to interpret my dream. Her interpretation was “You will travel a great deal.” That was all!

And coming to the infallibility of the Guardian, it took some time for me to accept the reality that this Sign of God on earth was infallible. I had witnessed the wonders and miracles that emerged from the unique and unparalleled services rendered by this “Priceless Pearl.” Shoghi Effendi’s infallibility became increasingly evident as I studied the Dawn-Breakers, God Passes By, and his other extraordinary books.

After a week at Geyserville Summer School, I was offered a room with kitchen facilities in Berkeley near the campus of the university in a rooming house owned by a Baháʼí, attended wonderful Baháʼí events throughout the Bay area, enrolled for a Master’s degree in economics at Berkeley, and found three different jobs.

DRAFTED INTO THE ARMY

In June of 1953, I was drafted into the Army, took a leave of absence from the university, and was sent to Fort Ord in California to train for the infantry to fight in Korea. At Fort Ord, I applied for “Conscientious Objector” status as a Baháʼí, was deeply questioned about my Faith by a board of officers, accepted, and transferred to the Army’s paramedic basic training facility, Camp Pickett, Virginia. There were about 24,000 soldiers training there at the time. By coincidence, I was invited by a fellow soldier to go with him to see a movie and stop by a canteen for some ice cream. Suddenly, someone shouted to me, “Bill Maxwell, what are you doing here, didn’t you go into the Navy?” “No,” I said, “I am here undergoing medical training as a conscientious objector.” He queried me further to discover that I had become a Baháʼí. He excitedly said, “I am here with a Baháʼí. Do you know Bill Smits?” “No,” I said. He then introduced Bill Smits to me. We embraced and so gradually became spiritual brothers.

The moment I arrived in South Korea, in May 1954, Miss Agnes Baldwin Alexander, then still pioneering in Japan, on and off, since 1914, assigned herself to be my principal mentor, writing voluminous letters almost every week with many quotations from the Baháʼí Writings. Shortly after my arrival in May, Bill Smits arrived, we were able to meet and began planning the first-ever in Korea a Commemoration of the Birth of Baháʼu’lláh on November 12, 1954. It was a glorious luncheon and harmonious meeting, the first-ever in Korea after Agnes Alexander’s many meetings in 1921 and 1922. Bill and I were joined on that occasion by about 10 others, several of whom somehow had found the Faith despite Korea’s horrific war from 1950 to 1953.

I was originally to be in Korea from 1954 to 1955, but the Asia Teaching Committee, managed by Charlotte Linfoot, an icon of an administrator, based in Wilmette, asked me to seek to remain longer. The Korean Civilian Advisory Corps, headed by an Army colonel, enthusiastically assisted me to get an appointment as an assistant professor of English at Chonnam National University, Kwangju, in southwest Korea, and thus I became the first pioneer to Korea. And I was the first army soldier honorably discharged in Korea to teach at a university. I married Mary Elizabeth, an American pioneer to the Caroline Islands, in 1960, in Tokyo. We remained in Korea until 1963. We welcomed many great teachers to Korea in that period, including Hand of the Cause, Agnes Alexander, and many pioneers, such as Phil Marangella, and Joy Earl of Japan. I also served as Auxiliary Board member for Agnes Alexander from 1957 until we left in 1963.

The first National Spiritual Assembly of Northeast Asia, 1957. Seated: Mr. Noureddin Mumtazi (treasurer), Mrs. Barbara R. Sims (recording secretary), Miss Agnes Alexander, later named Hand of the Cause, Mr. Phillip Marangella. Mr. Hiroyasu Takano (vice-chairman). Standing: Mr. William Maxwell, Chairman; Mr. Michitoshi Zenimoto; Mr. Hiroyasu Takano, Vice Chairman; Mr. Yadollah Rafaa; Mr. Ataullah Moghbel.

To this Assembly, Rúhíyyih, on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, wrote: “He is happy to see that (the) Assembly has represented on it members of the three great races of mankind, a living demonstration of the fundamental teaching of our Holy Faith.” This was his last letter to the National Spiritual Assembly of Northeast Asia, 1957. This was the only National Assembly at the time so representative, a model for many other nations in the future.

In Gambia, 1972. Left, Husayn Ardekani, Right, William Maxwell

EARLY NURTURING

While I have related how I grew into the Faith, I need also to say how I was nurtured into the Faith from my earliest days. A newborn child needs to be breastfed by the mother in order to survive. Those who attain spiritual birth too need to be nurtured, almost full-time. Some are nurtured by reading the Holy Writings and saying lots of prayers. While I too did the same, the greatest nurturing was from the love and guidance I received from many of the Hands of the Cause and great teachers such as Marzieh Gail and others who lived in or visited the Bay Area. In the early years of the Ten-Year Crusade, Berkeley alone had sent out over 40 pioneers to all parts of the world. And at the First Baháʼí World Congress, 1963, half of the Hands of the world seemed to be there to spread the fragrance of saintliness to those of us present. Those Hands, all of them, had a profound impression on me in my early years as a Baha’i. I attribute my ability to remain firm in the Covenant to their overwhelmingly positive influence. Here is the list of a few Hands of the Cause that I met in Chicago and later and was spiritually strengthened by what I learned from their presence and their words.

AMATU’L-BAHÁ RÚḤÍYYIH K͟HÁNUM

I must have been in her presence over a dozen times around the world from 1952 to the year of her death, January 2000. My first pilgrimage was in 1959 when I was chairman of the National Spiritual Assembly of North East Asia, headquartered in Tokyo and serving Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau as well as Okinawa which was then occupied by the U. S. military and not legally yet returned to Japan. In that pilgrimage, Amatu’l-Bahá sat about teaching me more of this very deep and wide-embracing Faith. I arrived at about 9:00 PM from Tel Aviv, Israel, and was immediately welcomed by the staff who offered me dinner. Suddenly and surprising the staff and residents, Rúhíyyih Khánum showed up. I later learned that this was her first visit to the Western Pilgrim House since the passing of Shoghi Effendi, November 4, 1957, in London. Over those intervening 18 months it was too painful for her to enter that house that had hosted so many deepening conversations with him. The central feature of that house was that very dinner table where the Guardian met and had dinner almost every night with the Western Pilgrims.

Suddenly a dark cloud of sadness reflecting the loss of Shoghi Effendi swept over me. I burst into uncontrollable weeping, an outpouring of grief that I did not know existed within me. Rúhíyyih Khánum tried to console me, caressing my back as I fell to the floor, overcome. Everyone understood the anguish and the mixture of sadness and joy to be near to the place where God time and time again revealed His love and knowledge to the world through Shoghi Effendi.

In London, in 1963, Amatu’l-Bahá had rented a large apartment for the First Baháʼí World Congress and invited about 35 people for an evening where she disclosed that she wanted to see a Baháʼí State somewhere in the world before she died. Chief among her guests were two of the youngest Hands of the Cause, Mr. Enoch Olinga from Uganda; and Dr. Rahmatu’lláh Muhájir, a Persian who first pioneered to Indonesia. Others included pioneers and believers from areas of the world where mass conversions had begun, The Congo, Bolivia, India, Vietnam, Korea, and one or two of the Pacific Islands. At his first opportunity, Jamshed Fozdar who had achieved enormous teaching success in Vietnam nominated that nation. I had the audacity to ask her why not a small European country such as Luxembourg. Her reply was something like this, “Luxemburg became rich by iron ore and the people’s minds today are cold like steel.” All of us there shared Madame Rabbani’s dream and hopes for accelerating mass conversion elsewhere. But we under-estimated the cold grip that materialism and other flaws held on the minds and hearts of our fellow humans.

Another highlight of that evening for me was to glimpse a scene that I thought could happen only in heaven. Two grown, mentally healthy men – Enoch Olinga and Dr. Muhájir gave each other a look of such love and admiration that I was totally stunned. Such things do not happen on this planet, a White man and a Black man unashamedly showing pure spiritual love for each other.

My association with Rúhíyyih Khánum continued in later years. She nominated me to the formal introduction of her to the over 2,000 people attending the Centenary Conference in 1968 in Palermo, Italy.

She and Mrs. Violette Nakhjavani stayed at our home in Nigeria in 1972 when she was on a round trip across tropical Africa. Our home was on the campus of the Government Comprehensive Secondary School, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Amatu’l-Bahá and Mrs. Violette Nakhjavani, wife of a member of the Universal House of Justice, arrived in their Land Rover. Two women who had traveled alone all the way across tropical Africa, and yet were still bubbling with energy. Their Land Rover was packed to the roof with supplies, a bird in a cage, a dog, and a lot of dirty laundries, food, first aid supplies, and spare parts. Our home was theirs for a week, while they rested, cleaned up, and got ready for the rest of their journey up the west coast of Africa from Nigeria to Freetown, Sierra Leone, and beyond.

A strange thing happened while they were in Nigeria. The manager of the Land Rover Company in Nigeria happened to have become friends with me, heard about these two adventuring ladies, and offered to replace the roof of their Land Rover at absolutely no cost for parts and labor, which he did. Thus, they gained about 80 cubic feet of extra space.

Among the stories they told while enjoying meals with us in their free evenings were these:

- When they crossed the border from the Cameroons into Nigeria, they did not notice the change of border signs and sped on through the border crossing without even slowing. A few seconds later they saw two heavily armed military vehicles chasing them with all sorts of lights flashing, and sirens blasting. The soldiers had to go pretty fast because Rúhíyyih Khánum had a well-known habit from her youth of speed-driving. They stopped and in seconds the soldiers aimed their AK47s within a few inches of their heads. They apologized, produced their papers, and explained to the incredulous Nigerian soldiers that they were not spies, nor insurgents, nor smugglers, but simply innocent tourists visiting friends and the Governor-General of Rivers State, Nigeria. They were believed and drove on not harassed any further, on into the country.

- There were few highways in tropical Africa. Often, they got stuck in mud or while crossing a shallow a stream. But they had a powered winch on their Land Rover that they could hook up to a nearby strong tree with chains and pull their vehicle out of a mud hole, or ditch, or whatever impeded their progress.

- In Port Harcourt, Mary, my wife, had begun writing a weekly Baháʼí column for the Nigerian Star, the top newspaper of the region. So the editor gladly featured a front-page story of Rúhíyyih Khánum’s major public speech in the area. Indeed, her speech was the top story of the week with a headline approximately this, “Source of World’s Troubles: The Educated People of the World.” The gist of the story that was run was to this effect, “It is the educated leaders of the world who create troubles for the world.” I did not hear any fallout from that provocative story.

I also had the privilege of introducing Amatu’l-Bahá to the Governor of Rivers State in Nigeria. Years later, I introduced this remarkable lady to the Governor General of Fiji in 1979 when I was living there during one of her visits. The very association with Amatu’l-Bahá enhanced my understanding of the majesty and nobility as well as the spirit of this Faith . She always had so many lessons to teach us.

CHARLES MASON REMEY

What a contrasting character! Mr. Remey was living in the Western Pilgrim House when I was on my first pilgrimage in May, 1959. We often fixed our own breakfasts at the same time and were in the kitchen often together. I do not remember a single kind word or a single tidbit of history from him. He at the time, in retrospect, was like a cold fish. He was expelled from the Faith in 1960 for “Covenant Breaking.” That is, he created a claim that he should succeed Shoghi Effendi as Guardian of the Faith. Other religions soon succumbed to such usurpation of authority. This religion is protected from such, we are promised, by both Baháʼu’lláh and The Báb. Mason Remey lived to old age and finally passed away as an unknown person, buried in a pauper’s field, in Italy, even though his father was an admiral in the U.S. Navy and had lived a life of privilege. His life shows that the Covenant of Baháʼu’lláh can never be shaken by any other power.

DOROTHY BEECHER BAKER

At the “kick-off” Continental Conference initiating Shoghi Effendi’s Ten-Year Crusade in April, 1953, Dorothy Baker was a principal speaker. Other than that I was never in her presence. But when she walked on stage there was an unmistakable aura of greatness. Just watching her on stage was sufficient proof to me that this event was reality itself, a touch of sanity in an insane world. One has to read the book “From Copper to Gold” to glean several aspects of this great soul.

AMELIA ENGELDER COLLINS

In my greatest period of spiritual agony, Geyserville, California, 1952, she was the Sunday Unity Feast speaker for about 1,000 Baháʼís and simply the bearer of divine love from Haifa. I never saw her again. Millie was a millionaire and yet kept a very low profile, expending much of her wealth for the Cause. We have the Collins Gate that Shoghi Effendi erected in her name, right at the entrance to the path that takes us to the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh, a spot Bahá’is consider the holiest spot on earth.

ʻALÍ-AKBAR FURÚTAN

I met him many times. I wish to recount two stories, both from the Intercontinental Conference that took place in Kampala, Uganda in 1968. At an outdoor gathering in Uganda there was a question from the audience, “Mr. Furútan, Please tell us about choosing a wife or husband?” Mr. Furútan answered, “Baháʼu’lláh recommends choosing a mate as far away as possible from your own genetic pool.” Mr. Furútan also talked about his meeting with Shoghi Effendi. He said, “Persian pilgrims used to talk about how overawed they were by the majestic presence of Shoghi Effendi. I downplayed such notions. One day when I was on my first pilgrimage word came that Shoghi Effendi wanted to see me privately in his room in ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s home. I went immediately, knocked and stepped inside. The moment I stepped inside I lost consciousness. When I came to, I was across the room, on my hands and knees trying to kiss Shoghi Effendi’s feet and he was lifting me up saying, “No, you can’t do that.””

LEROY CHAPMAN IOAS

In 1955, I was getting my honorable discharge from the Army to pioneer and teach at Chonnam National University, Korea. Despite having only $300 in my pocket, I wrote to Shoghi Effendi for permission to come on Pilgrimage, hoping that if he said yes, I could find the $1050 more needed. Instead, Rúhíyyih Khánum replied that “Shoghi Effendi thinks it would be better for you to pioneer and then later come to Haifa.” My salary was $30 per month at the University with no other source of income. But early in 1957, I had gotten a job with the U.S. Army in Korea with a salary of $9,000 per year and I got a letter from Leroy Ioas which read, “Dear Mr. Maxwell, we were going through Shoghi Effendi’s papers and found a note to invite you on Pilgrimage. We have reserved space for you beginning on 2 May 1959.” Shoghi Effendi knew exactly when I would have $1,350 in the bank. I never met Mr. Ioas but he was Shoghi Effendi’s “Right Hand Man” and forerunner of the kind of executives that the Baháʼí Faith will train to build a New World Order of competency and efficiency.

TARÁZ’U’LLÁH SAMANDARÍ

He was in the presence of Baháʼu’lláh and I had met him on a few occasions. In 1953, Mr. Samandarí graced the International Conference. I still had not gotten used to embracing men. He embraced me with such energy at his age where his beard was like a wire brush that I felt my face after the embrace to check if there were any blood. He was a small but extremely strong man. But his voice was like that of a giant. This man was probably as close in spirit and personality to Baháʼu’lláh as any normal man, other than ‘Abdu’l-Baha, can get. His prayers seemed exactly as Baháʼu’lláh would utter them, strong, powerful, reaching to heaven and into every heart.

GEORGE TOWNSHEND

I never met Hand of the Cause George Townshend. But his Auxiliary Board member, Mrs. Marion Hoffman, invited Mary and me to her home for tea near Oxford, England, in 1963 and told this story. In 1944, Shoghi Effendi had finished his monumental history of the first 100 years of the Babi and the Baháʼí Faith and send the manuscript to Mr. Townshend with three requests:

(1) Review and critique the language;

(2) Write the introduction; and

(3) Give the book its title.

Mr. Townshend immediately went to work on those three tasks. For task number one he simply wrote back that “You have lifted the English language to a new level (of precision),” if I remember correctly). I think he compared Shoghi Effendi’s refinement of the language to Chaucer’s.

For task number two he wrote an essay that scholars a thousand years from now will study. Here is an excerpt from that essay, that introduction, that has only one rival in history, that of the Muslim Ibn Khaldun, the world’s first sociologist.

“Slowly the veil lifts from the future. Along whatever road thoughtful men lookout, they see before them some guiding truth, some leading principle, which Baháʼu’lláh gave long ago, and which men rejected.” (God Passes By, p. xv) That Introduction was promptly dispatched to the Holy Land.

For task number three, Mr. Townshend was stuck. He received a follow-up urgent cable from Shoghi Effendi, “Going to press immediately, urgently need title” or words to that effect. Mr. Townshend was having a panic attack. He knew the importance of obeying Shoghi Effendi.

He could not conjure up a title no matter how much he reviewed his knowledge of Nabil’s Narrative or the histories of Thucydides or Herodotus or Tacitus or Edward Gibbon, nothing appropriate came to his mind. Another urgent cable came directly from Shoghi Effendi himself. Mr. Townshend went into a full press panic mode. Near to midnight, he walked out into his small garden, happened to glance up and there was a streak of fire across the sky, a falling star, a comet, “God Passes By” came like a bolt from heaven into his mind and he knew the title.

Although I had not met George Townshend, his books that I read created everlasting impressions within me. The book George Townshend by David Hoffman says the Guardian had sent messages to George Townshend through Hand of the Cause John Ferraby. Some of the notes of the Guardian to George Townshend say, “He is the best living Baháʼí writer…He is the pre-eminent Baháʼí writer”.

GENERAL S͟HU’Á’U’LLÁH ʻALÁʼÍ

I met him on a few occasions. General ‘Alá’í spoke no English. But I sat next to him at Mrs. George Lee’s sumptuous Garden Dinner Party in Singapore, following that Intercontinental Conference in 1958. What I received from him was simply human and heavenly warmth.

DHIKRU’LLAH KHADEM

I met him many times. He appointed me to the Auxiliary Board for teaching with responsibility for New England and Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1964. His frequent conferences with all his Auxiliary Board members, including his wife, were always inspiring and full of spiritual information. He was a scholar, very noble in character, simple and yet very dignified. I learnt from the book Zikrullah Khadem, the Itinerant Hand of the Cause of God by Javidukht Khadem, that when the Guardian passed away Mr. Khadem ceased to be a normal person, lost his appetite, and had no strength to attend the funeral. Hand of the Cause Mr. Faizi and other friends had to nurse and care for him. Such was his boundless love for the Guardian.

ADELBERT MÜHLSCHLEGEL

I only met him twice, once at a conference of Counselors with the Hands in Haifa and the next at another conference in Italy. I was very sad, that despite the efforts I made to meet him, we never had a conversation. I read this in the book Passing of the Guardian by Amatu’l-Bahá, “On Tuesday morning a telephone call was put through to the Hand of the Cause Adelbert Muhlschlegel, as Rúhíyyih Khánum had decided that he, a physician, one of the Guardian’s own appointed Hands, and a man known for his spirituality, would not only be able to endure the sorrow of performing the last service for the beloved Guardian of washing his blessed body but would do it in the spirit of consecration and prayer called for on such a sacred occasion.”

AGNES BALDWIN ALEXANDER

I had been in association with her since my arrival in Korea in 1954. In 1957, she appointed Mami Seto of Hong Kong, Zenimoto-san of Hiroshima, and me as her Auxiliary Board members. One story she told me: In 1923 before the Great Fire of Tokyo, some covenant-breakers came to Japan and tried to convince her that Shoghi Effendi was an illegitimate leader. They shook her faith to her very core. She prayed for a miracle to restore her faith and left for Kyoto for a visit with the Baháʼís there, many of whom were blind. The Great Tokyo Fire happened after an earthquake and burned a great part of the city taking 142,000 lives. She returned to her home and everything had been burned to the ground except the Kitab-i-Iqan by Baháʼu’lláh which was lying unburnt, open on the floor. She picked up that Holy Book and noted a passage that was unblemished, “It is for God to test the servants, and not for the servants to test God.” She shared her interpretation, “Never ask God for a miracle.” She later joined us in the winter/spring of 1963 to one of the two villages in Korea where mass conversions were taking place.

Here is a “miracle” attributable to Hand of the Cause Agnes Baldwin Alexander I witnessed myself. During the fasting period of 1963, Agnes Alexander wanted to visit one of the villages where mass teaching was underway, spurred earlier by Hand of the Cause Dr. Muhájir. So we rented two taxis and nearly all of us from Taegu and Ms. Alexander invaded the village and were exceedingly well received. Came time for lunch, we explained that we were fasting and would say some prayers while everyone in the village went home to have lunch. After lunch, no one asked about fasting and we dared not mention that practice as the earlier Baháʼís, most of whom were young with many being medical students, all of whom had had difficulty accepting the laws of fasting. But Koreans are among the earth’s most intelligent races and put 2 and 2 together without any of us mentioning the laws about fasting. They knew that Agnes was 88 years old, and was genuinely fasting at her advanced age with no negative effects. That example must have inspired everyone in that village to give up the superstition voiced by some early believers, “Koreans can’t fast.” The very next weekend several of us re-visited the village. The entire village of 930 souls, minus the children, were fasting and had accepted the Faith without being invited to enroll. Such are the powers that God bestowed upon the Hands on some occasions. O God, please lift-up from this darkened world people like the Hands You once raised up.

On an earlier visit to Korea, the Baháʼís had arranged for Ms. Alexander to give a public lecture at a major hall in Seoul. The new Baháʼí who had the best grasp of English, Oh Jae Dong, asked that she send him a copy of her talk so that he could study it ahead of time. She replied, “How do I know what I am going to say before I see the people?” It worked out fine. She spoke slowly and simply to the 200 or so people present in one of the popular halls in Seoul.

ABU’L-QÁSIM FAIZI

I met him a few times. In London in 1963, before more than 6,000 Baháʼís gathered for the First Baháʼí World Congress, Mr. Faizi announced, paraphrasing. “Baháʼu’lláh stated that the names of these nine men (the first nine elected members of the supreme authority of the Baháʼí Faith, The Universal House of Justice) were engraved in Tablets of Chrysolite from the beginning of time!”

After that historic Conference, my wife, Mary, and I took the two-hour train ride back to Oxford University where I had been enrolled by the Director of the Institute of Education, Mr. A. D. C. Petersen. At Oxford, I had also joined the Oxford Union, the ancient debating club, and had reserved a room for Mr. Faizi to speak to some of my professors and fellow students. There were no other Baháʼís at Oxford at the time to help me organize the meeting. About 40 people showed up, including Oxford’s premier professor of “Beliefs and Attitudes,” Professor Babbington-Smith.

The talk was exceedingly bland, to my disappointment, mostly about the twelve principles; nothing provocative such as “Christ has returned in full glory,” that some teachers liked to use in those days to wake up their audiences. Sensing my disappointment, Mr. Faizi patiently said to me. “if a person’s cup is full, you can’t pour anything more in it.” Mr. Faizi was a superior teacher, he could read people and know exactly how much to offer and then stop there. He taught me when to stop talking when delivering a public talk. Mr. Faizi was also highly respected as a man of great knowledge not only of the Baháʼí writings but also of the vast Islamic mystical and poetic writings.

JALAL KHAZEH

I had met him a few times. I first met Mr. Khazeh in Tokyo in 1957 when he represented the Guardian at the first Convention of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of North-East Asia. He then came to Korea and gave wonderful talks in both Kwangju and Seoul. Mr. Khazeh had an imposing physique, tall, large, and warm. During my pilgrimage to Haifa in 1959, he and I were sitting alone in the Eastern Pilgrim House and he was telling stories, most of which were funny. In walks, his wife says something that sounded rebuking and I asked, “What did your wife say to you?” He replied, “She said to close the gate to my stomach.” Mrs. Khazeh had heard him joking that “My wife’s name is “Jamal” which means “beautiful” and my name is “Jalal,” which means “glorious.” My wife is not beautiful, but I am glorious.” Then he burst into laughter. His penchant for laughter reminded me of stories of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá who loved to tell jokes, even in prison. He frequently reminded the American Baháʼís to use more humor.

In one our visits, Mr. Khazeh also told a story of his service in the Iranian Army as a colonel. One time he went on pilgrimage and Shoghi Effendi asked him about his service in the army and said to him words to this effect, “You are an expert in nutrition, how to feed an army. Many rural Baháʼís do not know how to prepare nutritious meals. In your travels teach the housewives not to boil all the vitamins out of their vegetables.” Mr. Khazeh said he fulfilled that mission wherever he went.

ENOCH OLINGA

I met him a few times, starting with the First World Congress in London in 1963. His address to the gathering disclosed some great principles of how to teach the masses which is essential for the Faith to convert a “doubting Thomas world.” Amatu’l-Bahá also invited some 40 friends attending the Congress, Enoch Olinga among them, to discuss mass conversion. I met him several other times as well, when I was a Counsellor for Northwest Africa, for example. Enoch Olinga, as we know, was already named the “Father of Victories” and had brought masses into the Faith. One of the families he brought into the Faith was the Tanyi family, originally from the Cameroons and which family pioneered to and anchored the Baháʼí Community of Ghana for many years. That family has remained firm in the Covenant because they were well-taught by Enoch Olinga. Enoch was like a spiritual fountain who also radiated a firmness in the Covenant from another level of existence.

DR. RAḤMATU’LLÁH MUHÁJIR

I met him several times. Korea can freeze human tissue so fast that many soldiers in the Korean war lost limbs, including my brother, Ludy Maxwell, who in 1952 lost a leg to frostbite. One day in late December of 1962 or January 1963, the Spiritual Assembly of Taegu was meeting in our home about 9:00 pm. There was suddenly a knock on our 10-foot-high gate. I went to the gate. A taxi had bought Dr. Muhájir to our home. Shocked out of my breeches, “Dr. Muhájir, how did you find my home?” “You are the only American living off the military base and all the taxi drivers knew where you live,” he replied. We of course enthusiastically welcomed him in, and the Assembly dropped all other matters to listen to him. He began to explain. “I was in northern Japan trying to talk with the Baháʼís. They were busy watching television while I spoke. I cancelled all my meetings there and flew to Seoul and took the train here to Taegu” We all were still in a state of shock. Then came the second shock. “It’s time for mass conversion here in Korea. Here is what you do. Find the remotest village in Korea and go there and seek out the purest and most respected soul in that village and teach him the Faith.” One of the very young new members spoke up, “My father is head of a village near NamWon. He is much loved. Can we go there?” We went there several times and people came into the Faith in masses. Such was the power Dr. Muhájir had in moving us into the mass teaching field.

There had also been other occasions at other times when I had met some Hands of the Cause of God coming together. At the Inter-Continental Conference organised in Jakarta, Indonesia in 1958 (and shifted to Singapore) I saw Leroy C. Ioas, Taráz’u’lláh Samandarí, Abu’l-Qásim Faizi, Harold Collis Featherstone, Dr. Raḥmatu’lláh Muhájir, Agnes Alexander, Shu’á’u’lláh ‘Alá’í, Dr. ‘Ali Muhammad-Varqá, Enoch Olinga, and Zikrullah Khadem. But did not coverse with them privately. During the Continental Conference held in Monrovia, Liberia, in January, 1971 I had met Amatu’l-Bahá and Dr. Muhájir. At the first Oceanic Conference held in Palermo, Italy in 1968, I met Hands of the Cause Ugo Giachery, the representative of the Universal House of Justice, and the Hands of the Cause ‘ Ali-Akbar Furútan, Zikrullah Khadem, Adelbert Muhlschlegel, Jalal Khazeh, Paul E . Haney, Enoch Olinga, William Sears, John Ferraby, Dr. Muhájir and Abu’l-Qasim Faizi. As Chairman of the Feast Program and as a Counsellor for Northwestern Africa, I had the bounty of introducing the Hand of the Cause William Sears who spoke on “The Day of God”.

These are glimpses of some of the Hands of the Cause of God who had exerted so many lessons into me. While I am thankful to have met them, there is still a great regret for not being able to meet the other Hands.

This is what we read from the Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “The obligations of the Hands of the Cause of God are to diffuse the Divine Fragrances, to edify the souls of men, to promote learning, to improve the character of all men and to be, at all times and under all conditions, sanctified and detached from earthly things. They must manifest the fear of God by their conduct, their manners, their deeds and their words.”

‘Abdu’l-Baha promised to send to American Baháʼís great tests. (He might have so warned others, I do not know.) But I know of no American Baháʼí who was not severely tested throughout his or her life. Marzieh Gail, for example, one of the greatest teachers and scholars that I knew well is no exception. Poverty hounded her most of her life, despite a wealthy background from the aristocracies of both the United States and Persia; despite great academic talents, and literary recognition, one of her history books, on the Popes in France, for example, was positively reviewed in the New York Times; and insanity ran in her family, etc. My own tests were unbelievably harsh and often extremely cruel. I survived and never once lost faith because, I believe, every Hand I met shared their deep and abiding and protective shield of faith with me as they did with everyone they met. Nothing like them has every happened in history. And is unlikely to happen again until the next Manifestation of God arises in a thousand years. We must forever thank Shoghi Effendi for his Hands of the Cause of God. They are gone but not lost. They live within us all.

With Mary, my wife and other believers in Seoul, Korea on the occasion of the observation of the centenary passing of Baháʼu’lláh , 1992

Professor William Maxwell, Ed.D.

Arkansas, USA

28 February 2021

Copyright@bahairecollections.com

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Professor William Maxwell accepted the Faith on 26 April 1952 in Oregon, USA, and was the first pioneer to South Korea in 1955 and served there for eleven years. He was also the first pioneer to northern Nigeria in 1967 and remained in Nigeria for 6 ½ years. He has also served in Fiji from 1977 to 1984 and in Albania from 2009 to 2012. He has given Baha’i lectures and workshops in over 60 nations in Asia, Africa, Europe, North America and Oceania.

As for his administrative involvement, he was Chair of the Local Spiritual Assemblies of Kwangju and Taegu in Korea; Raleigh, North Carolina, USA; Phoenix, Arizona, USA; Kaduna and Port Harcourt in Nigeria. He was also Chair of the National Spiritual Assemblies of Northeast Asia, Fiji, Korea; and a member of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States on two different periods between overseas work.

He served as Auxiliary Board member under Hand of the Cause, Agnes Alexander for North East Asia from 1957 – 1963; and under Hand of the Cause Mr. Zikrullah Khadem, in North East USA and Parts of Canada from 1964 – 67. He also served on the Continental Board of Counselors for Northwest Africa, from 1968 – 1973, with Husayn Ardekani, a pioneer from Iran, and Muhammad Kebdani, a native Berber of Morocco.

Professor Maxwell has taught at Baha’i Summer Schools and institutes throughout USA, Banff Canada, East Asia, the Pacific Islands, Hawaii, Albania, Kosovo, Croatia, Greece, and West Africa.

He obtained his Masters and Doctorate in Education from Harvard University.

For some of his academic and research publications: See: www.geniusdiscoveryacademy.com

A specimen of his television appearances is at YouTube: Education Talk/London/Professor Maxwell