REMEMBERING LIM KOK HOON

16 March 1944 to 5 January 2015

This is a story of Lim Kok Hoon, an unsung hero who quietly and as a lone-ranger decorated the pages of the history of the Bahá’í Faith in Malaysia, in his own unique ways. Among his several areas of service, he shall continue to be remembered in the annals of the Bahá’í Faith for rendering indelible services in the aboriginal jungles or Asli areas, and for single-handedly accomplishing the goals of the 9 Year Plan, which was translating Bahá’í literature into the Asli dialects of Senoi, Semai and Temiar dialects.

Kok Hoon as he came to be called, accepted the Faith at the age of 20 in 1964 through the late Mr. S. Nagaratnam while studying at the Sultan Abdul Halim College in Alor Setar. The Faith came to Kok Hoon at a time when he found his life totally hopeless with all the worst odds lined up against him, both at home and in school. Later he would say that it was the mercy of God that had rescued him from both the mental and physical torments and torture that he was enduring during his teenage day.

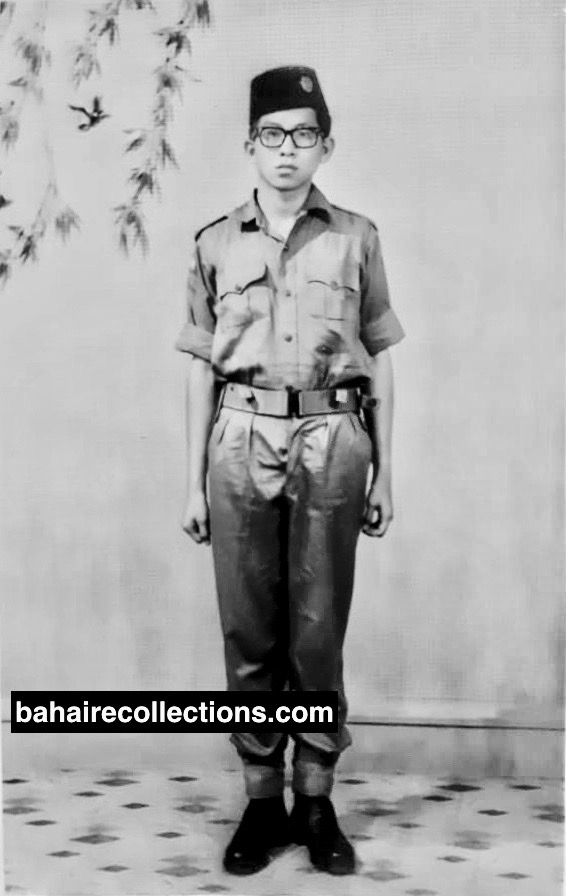

Kok Hoon was a very bright student who soon rose against all these odds. Even while at Form 4, he was the head of the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade, and at Form 6 was the editor of the school newspaper called “Suara Maktab.” While everyone else was busy panicking and studying for examinations, Kok Hoon would be cool and calm, working on the Suara Maktab. Since his home did not offer a peaceful and proper environment, Kok Hoon would study in his school until late at night. And he did pass well in all his examinations at the college.

Head of St. John’s Brigade, 1966

As soon as Kok Hoon accepted the Faith he joined his other Bahá’í friends in spending much time studying the Writings, with guidance coming from Nagaratnam. Kok Hoon’s first teaching activities were carried out in the company of Nagaratnam and Phung Woon Khing in Alor Setar and Jitra areas, often visiting the rubber plantation settlements. When Kok Hoon became independent, he undertook teaching activities in and around Alor Setar when he was able to ride a bicycle.

As Kok Hoon was picking up momentum in the teaching field, everything had to come to an abrupt ending. The moment Kok Hoon’s father came to know that he had accepted the Bahá’í Faith, he was beaten and thrown out of the house. Rather than losing hope in life, Kok Hoon dedicated himself to teaching the Faith. That opened a new phase in his spiritual life. His first services were when he went into the jungles at the age of twenty in 1964, at the behest of Hand of the Cause of God Dr. Muhajir. From 1964 to 1966 Kok Hoon made frequent visits to the Asli areas, starting with the Kampung Chang in Perak. The Kampung Chang experience opened his eyes. He saw the dire need of human resources to spread the glad tidings among the very receptive Asli believers and decided to dedicate himself to serve the Faith in their midst. Using Perak as the springboard, he later spread his wings into the Asli areas in the states of Kelantan, Selangor, and Pahang. He willingly and knowingly undertook this perilous path of service at a time when there was the grave danger of the banned communists and the soldiers still shooting at each other in the jungles. Although he knew that any inadvertent encounter with either of them meant instant death, he still courageously went ahead leaving his fate in the hands of Bahá’u’lláh traveling by foot, from one Asli village to another which sometimes took two full days to reach the destination.

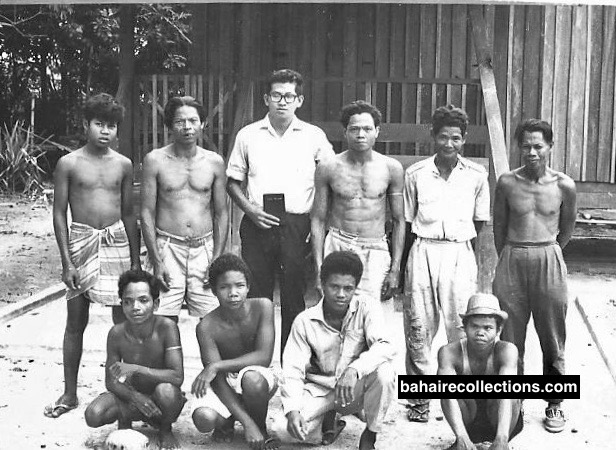

From urban dwelling into the Asli jungles.

It was not an easy path of service for a youth, born and brought up in a town, and now having to live in a very hostile environment. The terrain was so vicious that by the time he reached the other village his shoes would be torn into shreds and he often needed another pair to walk back. To move from one village to another involved traversing thick jungle foliage, and getting exposed to wild animals, leeches, and snakes. There were times he slept the nights on the trees to avoid soldiers, communists and wild animals. As for food, he had to satisfy with whatever food he could find and even surviving several times on bad food, and at times no food at all. There will be only water with no salt or spice, and the food he ate tasted way off from what he had consumed in the towns. When no animal was trapped, he lived on tapioca that was either baked or smashed into a coarse flour. With Kok Hoon consuming tapioca for breakfast, lunch, and dinner and sometimes supper with no salt or sugar, his feet would swell up. Kok Hoon’s intention in sharing his hard life in the jungles was not to complain but to stress that one has to be happy in the teaching field, whatever comes by.

With Asli friends in Kampung Chang, Perak

Kok Hoon spent his time in the Asli villages, teaching them the basic tenets of the Faith in simple terms. He stressed the importance of chanting prayers and introduced basic laws. He himself used to chant the Tablet of Ahmad from memory in their company in the Malay language. Kok Hoon used to relate many stories of the Heroic days and stories related to the life and sufferings of Bahá’u’lláh, and through this he wanted them to develop the love for the Blessed Beauty.

In 1966, Kok Hoon moved into the town of Petaling Jaya to take up a degree course in University Malaya. He did get a place in University Malaya, and while studying involved in an aggressive proclamation of the Faith. But he could not continue his studies owing to financial problems. Yet, during that very short spell at University Malaya, a dramatic event took place. There was a group of students who humiliated, embarrassed and insulted Kok Hoon all because he proclaimed the Faith such an audacity. He was tolerating for several days until things crossed the threshold. One day they yelled “Bahá’í” as he entered the lecture hall. Kok Hoon felt so hurt that he recited the Fire Tablet to relieve him of the agony his heart was going through. His prayer was instantly answered. The very next day news reached him that the group of those notorious students met with a car incident, and all of them died on the spot. Kok Hoon was plunged into further sorrow as that was not what he had prayed for. He was sad for several days, until one day a close friend consoled Kok Hoon that ours is the duty to pray, but God decides the nature of answer for our prayers. Kok Hoon felt slightly relieved. But he came to a firm conclusion. That would be the first and last time he would recite the Fire Tablet. Kok Hoon shared this episode only with selected friends.

Kok Hoon’s coming to Petaling Jaya was useful in another way. When Kok Hoon came into Petaling Jaya in 1966, it was a period of inactivity there, and the Local Spiritual Assembly was at its weakest. It was reported that from 1964 not even a single soul accepted the Faith. It was at this time that the dynamic Kok Hoon came to Petaling Jaya. When Mr. V. Theenathayalu from Alor Setar was secretary of this Assembly in 1967, he was re-organizing the administrative affairs of the community with a good filing system. Kok Hoon got hold of the list of the old Bahá’ís and went on a motorcycle with Theenathayalu to visit them for the purpose of consolidating them and reviving the community. He and Theenathayalu who were already close friends from the Alor Setar days. Things started to turn out for the better in stages.

When Hand of the Cause of God Dr. Muhajir came to Malaysia in April 1967 and heard about the great services rendered by Kok Hoon in the Asli villages in the state of Perak. Dr. Muhajir immediately requested him to concentrate on a special task for the Faith, which was the completion of the tribal translation goals under the Nine-Year Plan for Malaysia. It was on the request of Dr. Muhajir and his love for the Blessed Beauty that emboldened Kok Hoon to single-handedly accomplish the one goal of the Nine-Year Plan, which was translating Bahá’í literature into the Asli dialects of Senoi, Semai and Temiar dialects. Kok Hoon held back this task owing to several other commitments. The Nine-Year Plan was ending in 1973, and the national institution reminded him that they were relying solely on him to win this goal. Kok Hoon sat down and completed the task on time and with distinction, winning the hearts of the Supreme Body, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Malaysia, and of course Hand of the Cause of God Dr. Muhajir. It was learned later that Kok Hoon had knowledge of eight dialects of the Asli people.

Kok Hoon once again set off to Bidor area in the state of Perak, this time for two months, effective 7 April 1967. Upon completion of the two months in Bidor, Kok Hoon moved on to concentrate in the Hulu Langat and the Kuala Langat areas in the state of Selangor. Kok Hoon moved with those simple people and soon won their love. Kok Hoon not only understood the culture and way of life of the Asli believers but became very much part of them. He was successful in bringing in several thousand Asli people into the Bahá’í fold in forty-eight villages from the Hulu Langat and Kuala Langat areas in the state of Selangor.

Whenever Kok Hoon came out of the jungles in the Hulu Langat area, tired and broken, it was the late Appu Raman who cared for Kok Hoon and treated his wounds. Whenever Kok Hoon reached Appu Raman’s residence in Cheras, at times during the early hours around 3 am, he did not bother to knock the door. Appu Raman would see him in the morning, sleeping on the doormat with the family guard dog, which never barked as it too had befriended him through his several visits. Such was his humility. Once out of the jungles, Kok Hoon consumed much salt water to replenish his body system, rather than visiting a doctor, as there was no money in his pockets.

Other than periodic visits to town, Kok Hoon had lived in the jungles for two years from early 1966 to over 1968. But he kept visiting them intermittently, and always found some conversation at national conventions. Many urban believers who visited the Asli areas in Perak state after Kok Hoon were simply amazed to learn of the amount of work he had done and the love he had won from them. They kept enquiring about the whereabouts and welfare of Kok Hoon. No one came out of the Asli areas without hearing the victory stories of Kok Hoon. To this day he is well remembered in the Asli areas. Whenever Bahá’ís from urban areas visit the Asli areas, the old-timers in the Asli villages still relate the great services and traces left by Kok Hoon. He had left behind a path of service for all Asli teachers to emulate. He loved them dearly, and they too loved him as the member of their own family. Kok Hoon often said that the only way to win the hearts of those simple people was to love them sincerely and with all your heart and be part of them. Kok Hoon dedicated himself to teaching the Faith in the Asli areas with full devotion, passion, obsession, determination and energy, and throughout his life his love for the simple people in the Malaysian jungles never diminished. When asked on the secret behind his success in the jungles, he said, “When you say you have brought the message of love, you should shower true love upon them until they feel your sincerity.”

While carrying out Asli teaching in Selangor, Kok Hoon frequented the National Bahá’í Center in Kuala Lumpur, where he spent much time sharing his success stories with S. Vasudevan, Secretary of the National Spiritual Assembly, who was residing in the Centre.

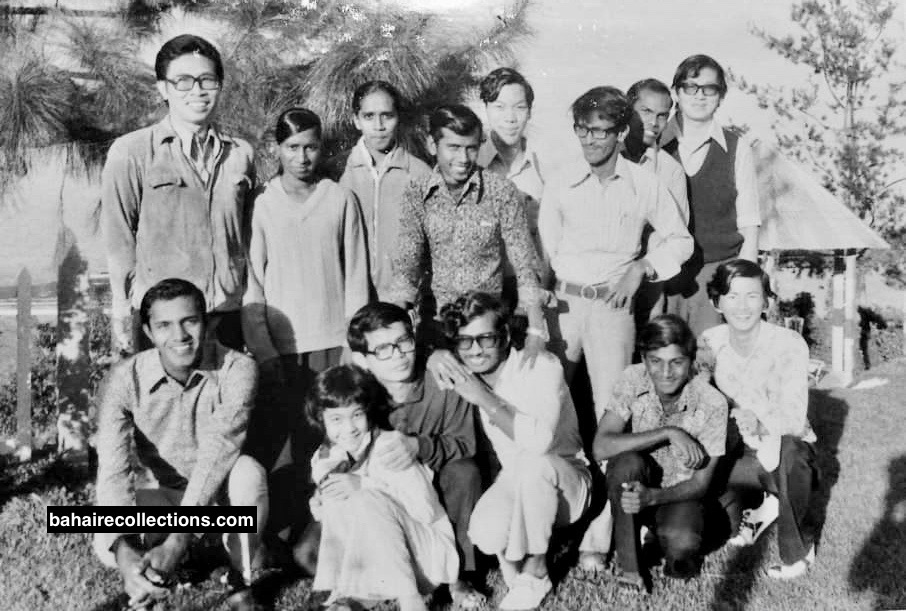

Kuala Lumpur, early 1967. Kok Hoon is seated with S. Vasudevan. Standing at extreme left is Kit Yin Khiang, Malaysia’s first pioneer to Taiwan, with Lee Wai Kok next to him. At extreme right is Sabapathy, who passed away in Mozambique.

Kok Hoon also served in other capacities. In 1967 he served on the National Bahá’í Youth Council. When a Teaching Conference was held at the Aun Hwa Chinese School in Tanjung Piandang, in May 1968, Kok Hoon spoke in simple and yet impressive Malay. This was a conference organized by the State Teaching Committee of North Perak and attended by Bahá’ís from Bagan Serai, Alor Setar, Taiping, and Penang. The estate communities around too participated in this conference.

But Kok Hoon was always on the move. On 1 September 1967, he came back to Alor Setar to take up his first job in the Income Tax office. From Alor Setar Kok Hoon was transferred to Penang in December 1967 where he stayed until 1974. It was while Kok Hoon was in Penang that Hand of the Cause Mr. Abul Qasim Faizi visited Malaysia in 1968 to attend the South East Asia Regional Youth Conference held in Kuala Lumpur. In this trip, Mr. Faizi had desired to visit the Asli believers in the jungles, and Kok Hoon’s services became a natural choice. Kok Hoon drove down to Kampung Chang in the state of Perak in his newly purchased Peugeot car. When Mr. Faizi arrived at Kampung Chang hundreds of tribal friends from several villages had come to welcome Mr. Faizi, having walked several hours through hills, rivers, and thick jungles. At that conference, many mothers stood carrying their infants in their hands. There were children flocking around Mr. Faizi. Seeing many children, Mr. Faizi spoke about the importance of education and training for the children. As an expert in the Senoi and Temun-Belanda dialects of the aborigines, Kok Hoon translated the talks of Mr. Faizi into those local dialects. Kok Hoon later informed Mr. Faizi in his private conversation that the tribal believers could feel his love for them.

Hand of the Cause of God Mr. A. Q. Faizi with Asli believers at Kampung Chang, Perak.

But this gathering faced an urgent problem which Kok Hoon did anticipate. A large number of Asli believers who had come to visit the Hand of the Cause had to be fed. There was none who was able to come forward to prepare food for them. Kok Hoon had only RM 500 in his pocket, which was set aside to be paid as an installment for his car for that month of December. But the situation came to a point where he had to either take care of the Asli believers or have his car repossessed. He did not want to lose the hundreds of believers and being ridiculed by the hundreds more of non-Bahá’ís who had gathered to see Mr. Faizi. He acted fast. On getting the pulse from the ground, Kok Hoon drove into the nearby town of Bidor and bought one sack of rice, several tins of sardines, onions, chilies, dried fish, coffee, sugar and biscuits with the only cash he had. With the plenty of food and drinks that Kok Hoon brought, a carnival-like atmosphere was set in at Kampung Chang. With this enthusiasm, a new idea came upon him. Kok Hoon resorted to open-air teaching. With the light of kerosene lamp, he taught the whole night until morning and no less than 500 people, including the newly married wives or husbands of the believers, came into the Faith. The next morning, he drove back to Penang to surrender his car to the car re-possessors and took to cycling to the office for many months to come.

The time came for Kok Hoon to settle down. Kok Hoon was a firm believer in inter-racial marriage. He was having an Asli girl in mind but had been postponing making the first move. But when he was in Penang that Kok Hoon was introduced to Miss Chow Kim Foong, at the Penang Bahá’í Centre at 42, Peel Avenue. Chow Kim Foong accepted the Faith in 1964, through Khoo Siew Teh. In the words of Kok Hoon, after meeting Miss Chow Kim Foong, “My head started to spin, and my heart started to throb.” He spent a few days saying the Tablet of Ahmad, beseeching Bahá’u’lláh to guide him to the right girl destined for him. Bahá’u’lláh paved the way and he was guided. After a year of courtship, Kok Hoon and Chow Kim Foong were married on 25 January 1970, at Penang Free School Hall with Counselor Dr. C. J. Sundram conducting the wedding.

Counselor Dr. C. J. Sundram conducting the wedding.

Following the wedding, he took his wife for a honeymoon, and that was to the Asli village of Kampung Chang. His heart was always for the Asli people. Chow Kim Foong fully understood the love her husband had for the Faith and the Asli believers. She became his strongest supporter and companion. This couple was blessed with a boy and a girl. They named their son Jalel Lim Boon Aik, and daughter was named Joanna Lim Mei Lin. Acutely aware of the problems he himself went through during his childhood days, he ensured his children got the best education. His daughter Joanna especially got a scholarship from Canterbury University in New Zealand and pursued her PhD in Education, since is lecturing there since graduating in 2017.

Honeymoon trip to an Asli settlement, Kampung Chang

His stay in Penang from 1971 to 1974 won unprecedented victory for the Cause in the island. He rented a house in Gelugor and worked his own way for the development of the Faith. For a long time, Penang island had a “One island-one Assembly” situation. A new Local Spiritual Assembly in Glugor was formed in 1972, with its centre at the home of the Sundrams at 3, Minden Heights and the Local Spiritual Assembly in Georgetown had its centre in the home of Lily Jansz at 21, Lim Cheng Teik Square. Kok Hoon saw that Penang had 16 communities and was, therefore, eligible to have 16 separate Local Spiritual Assemblies. He started to work on establishing 16 Assemblies. It took Kok Hoon 4 years from 1971 to 1974 to achieve this target, doubling each year the number of Local Spiritual Assemblies from 2 to 4 to 8 and finally to 16. He concentrated in the multiplication of communities through teaching activities in the Chinese speaking areas. Among those Kok Hoon mobilized for the expansion program in Penang were Soh Aik Leng, Wong Meng Fook, Lily Janz, Tan Lee Soo Hock, Jimmy Seow, Tan Gaek Seng, Ah Teik, Albert, Gopal, and Sunny Lim. The targeted 16 Assemblies were established in 1974. This momentous achievement was noised abroad when the story was published in the November 1977 issue of the Bahá’í News Magazine of the United States of America. It read, “There are now 16 Local Spiritual Assemblies on the island of Penang, four kilometers (two and one-half miles) off the coast of Malaysia. None was there three years ago.”

There was one more first-time effort that Kok Hoon initiated in Penang in 1972 was the first Bahá’í Conference in the Hokkien dialect, which was first mooted by Kok Hoon himself. Wong Meng Fook from Singapore says, “When Kok Hoon took up this matter with Assembly the institution happily and immediately gave its approval.” Then the majority of the participants were the youths of Penang who had just accepted the Faith. This conference was held at the home of Mrs. Lily Jansz at 21, Lim Cheng Teik which was also the Bahá’í Centre for Georgetown community. Kok Hoon took on the task of translating a selection of the Bahá’í prayers from English into Hokkien dialect, using combination of alphabetical words to capture as close as possible the sounds and pronunciations for their equivalent Hokkien names such as “God,” “ The Almighty,” “The All-Knowing,” and “The All-Wise.” The participants found the exercise full of fun and yet enjoyed that historic get-together. Among the friends who participated were Mrs. Lily Jansz, Mrs. Lily Seow, Mrs. Susie Wong, Mr. Yin Hong Shuen, Mr. Soh Aik Leng, Mr. Anthony Boon, Mr. Wong Meng Fook, Mr. Tan Lee Soo Hock, Mr. Wong Cheow Wing, Mr. Tan Hui Chuan, Mr. Lim Chye Choy, Mr. Jimmy Seow, Mr. Lim Kok Hoon, Miss Loh Wan Wan, Miss Loh Lee Lee (at the time of writing this story was Counselor Dr. Lee Lee Ludher), Miss Chung Chiew Lai (Mrs. Julie Pau), Miss Yap Ai Nee, Miss Padma Sundram, and Miss Ong Lean Im. Among the children who participated were Chong Poh Chean, Chong Siew Lean, Wong Sow Fen, Wong Meng Kee, and Malini Sundram.

First Hokkien Conference, 1972. Leaning on the wall towards the right is the organizer Lim Kok Hoon. Wong Meng Fook is at extreme right, and the host Lily Jansz is at extreme left.

First Hokkien Conference, 1972. Leaning on the wall towards the right is the organizer Lim Kok Hoon. Wong Meng Fook is at extreme right, and the host Lily Jansz is at extreme left.

While in Penang, Kok Hoon had also been assisting in the development of Nibong Tebal and Parit Buntar and Bandar Baru situated on the mainland, and to the south of Penang.

Next, Kok Hoon came to Taiping town in Perak. From 1 January 1975 till 1982 Kok Hoon worked as Inland Revenue Officer. R. Kanniappan was already a great pillar of the Faith in Taiping when Kok Hoon arrived in that community. Kok Hoon used Taiping as a springboard to serving in many surrounding places. There he worked tirelessly on the expansion program. The target this time was every town, village, and estate to have Local Spiritual Assemblies; it was a blanket coverage from Kuala Kangsar to Parit Buntar, Pangkor Island to Grik and Keroh. He formed and led teaching teams to these areas to revive the lapsed Assemblies and also to form new ones. Sukumaran Sangaran Nair says,“Kok Hoon was very organized and highly systematic in his approach to teaching the Faith. He set up an “Operations Room” at the Taiping Centre in which he visually mapped out teaching activities on a wall-mounted map. His approach reminded me of one that a geographer would take. Long before software tools such as GIS (Geographical Information Systems) and Google Maps introduced the idea to the public at large, he was already adept at using mapping tools, albeit on paper, as a planning tool and for insights into the situation on the ground where teaching was concerned. At any time anyone wanted to get the big picture of what’s happening to the Faith in Taiping and it’s surrounding neighborhoods, all one needed to do was look at the map. His meticulous record keeping and documentation of all activities related to the Faith in Taiping will prove valuable to the future generation of Bahá’ís.”

Within a span of 4 years, Kok Hoon managed to add another 22 Local Spiritual Assemblies in northern Perak with undivided support coming from the believers in Taiping area. He was Chairman of the Local Spiritual Assembly of Larut Matang and Kamunting during the time he was in Taiping area and proved to be an able administrator and planner of several teaching activities. The Taiping friends remember Kok Hoon reciting ardent prayers, especially the Tablet of Ahmad before undertaking any kind of Bahá’í activities. He also attempted to memorize prayers in the Tamil language.

Assembly of Taiping, 1975. Seated L-R: Mrs. Chow Kim Foong, N. Ramasamy, Lim Kok Hoon, R. Kanniappan and Mrs. Gunaletchumy Perimal. Standing L-R: Shanmugam, Kumar, Arputhaseelan and G. Perimal.

Taiping, 1976. Yankee Leong, Lim Kok Hoon, Jalel Lim Boon Aik, and Chow Kim Foong.

Kok Hoon’s focus within Taiping town was on bringing back the old-time Chinese believers in Taiping, which he did successfully. He paid some pocket money to a Tamil and a Chinese travel teacher to carry out full-time teaching work in the Taiping area. The Tamil travel teacher was T. Maniam, Homeopathy Practitioner in Butterworth, and the Chinese friend was Ah Seng from Kuala Sepatang. Kok Hoon also bought a bicycle for Maniam to move around in Taiping. Kok Hoon organized teaching teams. He roped in local believers like Arputhaseelan, N. Ramasamy and G. Perimal as well. He started with a Volkswagen and later a Fiat car in which took them for teaching trips. With the assistance of Ah Seng, the community in the town of Bagan Serai was revived. Soon many Chinese accepted the Faith. Several Chinese School headmasters, teachers and heads of the Chinese Chambers of Commerce enrolled into the Faith. A strong Chinese base was established in Taiping. One member of the Board of Governors of the Hua Lian Secondary School also accepted the Faith. Kok Hoon used his influence to rent a bungalow in Maxwell Hill belonging to Perak Royalty and took along the believers for retreats to read the Writings and plan activities. Mr. Wong Meng Fook and Mr. Soh Aik Leng from Penang and Mr. Yee Wai Cheong from Butterworth too joined them.

Retreat at Maxwell Hill, 1976. Squatting L-R: N. Ramasamy, Chong Siew Lan, Soh Aik Leng, Selvam, and Yee Wai Cheong. Standing L-R: Wong Meng Fook, Mrs. Manickam, Mrs. Gunaletchumy Perimal, Jokim Robert, Kumar, Arputhaseelan and Lim Kok Hoon.

The believers were all along gathering in the homes of believers. Kok Hoon saw that the community had grown big enough to rent a centre. At the end of the 1970s, Kok Hoon initiated the renting of a Bahá’í Centre in Taiping. He donated his own cabinet and initiated a library as well. Soon Taiping became one of the most active Bahá’í communities in the state of Perak. Kok Hoon also initiated communications with the authorities to acquire Bahá’í burial grounds, which was followed up by later believers.

Kok Hoon’s stay in Taiping was also marked with a period of intense teaching in the rubber plantation settlements or estates. He took along Tamil speaking friends to nearby estates. At Soon Lee Estate in the Bagan Serai area, Kok Hoon became a close friend of Mr. Gopal. Gopal’s father Mr. Ramayah, was a supervisor in the estate and a strong supporter of the Faith, though not a believer. Kok Hoon set up a dynamic team and opened up several estates in northern Perak. Among them were Chersonese Estate, Malaya Estate, Highbornia Estate, Jebong Estate, Lauderall Estate, Widsor Estate, Kati Estate, Krian Road Estate, Batu Kurau Estate, Sin Wah Estate, Pulau Estate, Buluh Estate, Eagle Hurst Estate, and Pondok Tanjung Estate. This team also went to open up the Port Weld Fishing Village and Kampung Baru Ulu Sepetang. In all these trips it was Kok Hoon who would foot the bill for all kinds of expenses. Kok Hoon’s success in winning the hearts of the simple people in the estates all because he was down to earth and mixed around without any prejudice. He would sit down on the floor with them and partake of their coffee. He would carry along the Feast Newsletters issued in the English language and translate them on the spot into Malay. And he would appear at the Feasts held in the estates dressed up in the traditional Indian dress of dhoti (called Veshti in the Tamil language). The estate people simply admired, loved and flocked around him. Kok Hoon’s stay in Taiping was a period of dynamism, and full of personal sacrifice on his part.

From Taiping Kok Hoon gave assistance to the Bahá’í community in Ipoh town as well. This town is located south of Taiping. Kok Hoon played an important role in the purchase of the Bahá’í Center of Ipoh town at 12, Jalan Rajawali. The Bahá’ís of Ipoh were desperately looking for RM 1,000 to be paid as the down payment for a terrace house costing RM 27,900, to be used as a Bahá’í Centre. Just 24 hours before the deadline, Mrs. Theresa Chee from Ipoh rang up Kok Hoon in Taiping informing him of the dilemma. Kok Hoon who loved Theresa Chee immediately rushed down to see Theresa Chee with RM1, 000, not in one bundle of notes, but in loose changes and a lot of shillings. With that cash that came in on time, the believers of Ipoh booked the link house, which cost extra by RM1,000 all because it was situated facing a beautiful field. That house was purchased in 1976, and to this day Theresa Chee remembers the timely help by Kok Hoon, and always had a fond liking for him. Theresa’s husband Mr. Chee Ah Hin was a shy and reserved believer. Kok Hoon befriended him and they met up often and became best of friends.

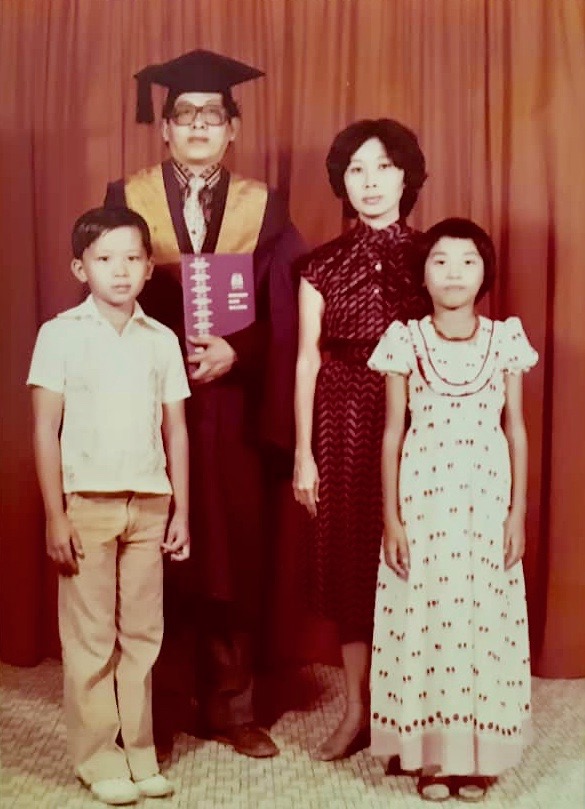

Having done his part for the Cause when the call came, Kok Hoon resumed concentrating on his tertiary education that was left out a decade ago. In 1976, while at Taiping Kok Hoon enrolled into the Universiti Sains Malaysia in Penang as an off-campus student to formalize the unschooled approaches he had undertaken earlier to translate Bahá’í literature into the Asli dialects. He was not entering university to have a degree attached to the back of his name, but only to fulfill the tasks assigned to him under the Nine-Year Plan. At the university, he took Social Anthropology, and with that knowledge he had gained, he kept visiting the Asli villages to carry out formal researches into the Asli’s concept of the afterworld and their funerary customs, traditional healing, their concept of the values of hot and cold foods and on shamanism and black magic. Kok Hoon was also studying the prospect of going to other parts of Southeast Asia to teach the tribes. Through the university library, he studied the tribes of northeast Thailand, the Shans, Chins, Karens, Meos, Akhas, Lisus and the Montagnards of Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. One of Kok Hoon’s lecturers was so impressed with his widening knowledge and progress in the subject that he offered to assist him in doing a Master program. But Kok Hoon declined the offer, thankfully. Kok Hoon graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Social Science in July 1982. His thesis, the first of its kind was widely referred to in several of the academic circles, to this day. After acquiring this degree, he would say, “When the call came, I took care of the Cause of God; and when my time came, God took care of my cause.”

With the family as a fresh graduate, July 1982

In 1982 Kok Hoon came to work in Kuala Lumpur for a period of two years. In this short period, he took along Tamil speaking friends from Kuala Lumpur, including the late Anthonysamy to visit several rubber plantation settlements in the Kuala Selangor areas to teach and deepen the believers.

It must be noted that wherever Kok Hoon was residing his heart was always glued to the spiritual welfare of the Asli people. In 1982 the Asli friends in the jungles of Perak were placed under restricted movements. Kok Hoon feared the possibility of those believers losing their spirit and finally leaving the Faith. Their spirit was already reported to be at the lowest ebb. He came up with a brilliant individual initiative. He crafted a strategy to take them out of curfew areas and train them at the Ipoh Bahá’í centre on Esselmont’s “Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era.” The target group was youths below the age of 16. In this fortnightly program spanning over 15 months, a total of 50 children and adults were trained at Ipoh. Later this was carried out in the Selangor area with the training taking place at the old Bahá’í center in Petaling Jaya. Here a total of 44 children and adults were trained fortnightly. Kok Hoon himself cooked the food and provided the bus fares to and fro. In that 15-month period, Kok Hoon did not send a single cent to his family, and he was proud of his wife who understood his heart only too well. He spent quite a huge amount to ensure the success of the training program- all for the love of the Asli people, the Faith, and the Blessed Beauty.

Kok Hoon retired from service in 1982, with a name for himself at the Income Tax Department. While at the Income Tax Department Kok Hoon was recognized for the speed and diligence with which he discharged his duties. He would complete in a few hours what would take an average officer some eight hours to complete a very difficult tax case. He mastered the art of detecting loopholes and gaps deliberately left out in the tax returns. There had been incidents where people had attempted to offer him money to have their taxes reduced, and Kok Hoon had threatened them of reporting to the nearest police station, with the usual stern look and penetrating eyes that was of him. Never was he embroiled in a corruption scandal, and neither was he caving into demands or pressure of any kind. Although Kok Hoon had all the qualifications to rise higher in his career, he lost out in his rightful promotions, which was not surprising in government service, given the kind of prejudiced work environment.

Kok Hoon returned to Taiping in 1984, and in 1986 was settled in the town of Klang. In the same year, he went to Subang Jaya where he resided till his passing. In Subang Jaya, Kok Hoon was actively involved in community affairs, often volunteering his services in various fields so long as his health was kind to him. As a very prayerful person, Kok Hoon used to organize prayer sessions in his home on Sunday mornings. Following the prayer sessions, he would go deep into the Writings and lead intelligent discussions. Lum Weng Hoe, who was secretary of the Local Spiritual Assembly of Subang Jaya community for several years had been communicating with Kok Hoon from about 1995 to 2014. Lum recollects, “He would express himself without fear or favour, carried out his own mass Teaching Plans in the way he knew best. He would visit the Kuala Selangor Chinese Fishing Villages where he made lots of friends and felt at home with them. He would convert his car into a make-shift tent and camped at the coastal towns of Sabak Bernam and Sungai Besar for days and invited the friends to join him. When no one turned up he went alone. At one stage he even drove his “Make-shift Tent” car (his mobile Hotel as he called it) all the way up to Hat Yai, Thailand for a teaching trip that lasted a few months. He even had his house car porch converted many times to accommodate a place to hold firesides and deepening classes with a Jacuzzi and a Hanging Garden, flower beds planted with vegetables for distributing to the community he loved. He had his own way of contributing to the community he belonged to. He was a legend in his own way.”

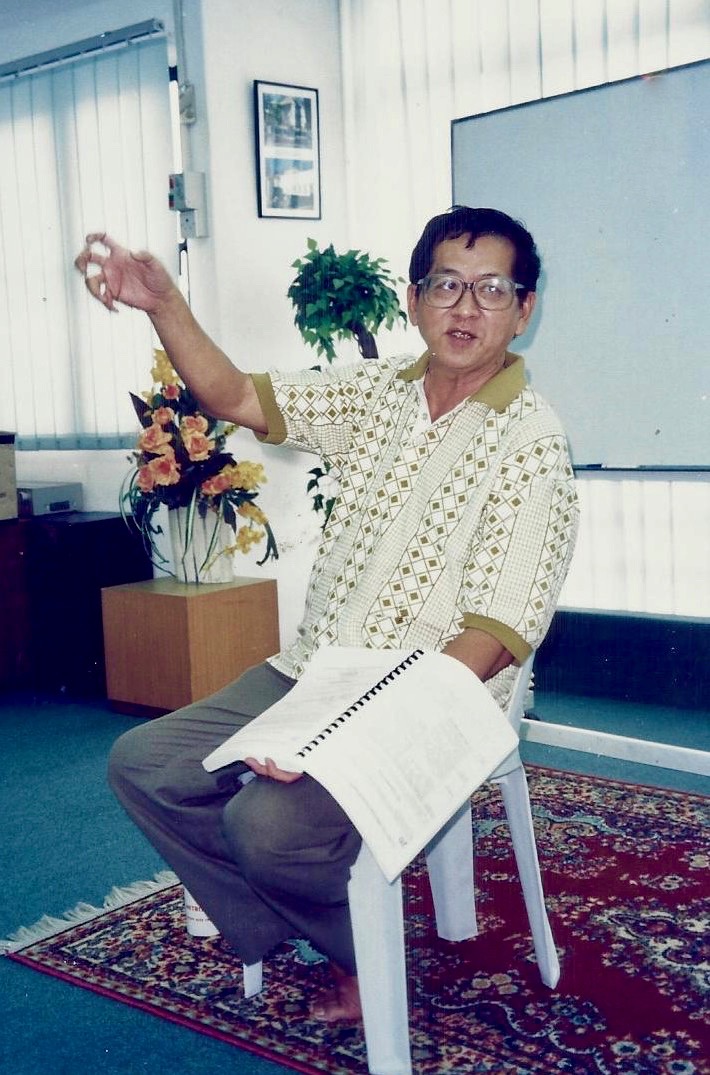

Kok Hoon conducting some training at the Subang Jaya Bahá’í Center, June 1999 (Photo credit: Lum Weng Hoe)

Although Kok Hoon went on optional retirement from Government service, he continued working in a private firm, and finally set up his own Tax Consultancy firm. From the earnings flowing in he was still able to serve the Cause as effectively as before, visiting the Asli friends in the jungles in Perak and those from the estates and fishing villages in Selangor. Kok Hoon loved to travel places. He was happy to have traveled to Bali and Lake Toba in Indonesia, Saigon in Vietnam, Sydney in Australia, and his ancestral home in Fuchou, China.

Dressed up as Balinese dancer. Always dared to be different.

The one place where he had left his heart was the holiest spot on earth for the believers. He had always wanted to go for pilgrimage. His prayers were answered, and he undertook nine-day Pilgrimage in 2008. Throughout the pilgrimage period, Kok Hoon was seen to be in his own world, lost in a meditative mood. Owing to failing health and feebleness he found it difficult to walk and keep pace with others in the pilgrim group. He was always the last to arrive, but the bus driver was kind to wait for him to board the bus. During visits to Bahji, Kok Hoon spent most of the time praying in the inner Shrine of the Blessed Beauty. When the bus departed for the hotel with other pilgrims, Kok Hoon stayed back at Bahji and kept praying in the inner Shrine, until the doors were closed. He would be the last to walk out and arrive at the hotel by taxi. Even on the day allocated for rest during the mid-point of the pilgrimage period, Kok Hoon went to the Shrine of the Blessed Beauty early in the morning and returned late.

After undertaking the pilgrimage, Kok Hoon still moved around visiting friends. He took along Dr. Kang Cheng Khay to visit Theresa Chee in Ipoh. Kok Hoon was happy to learn of the many services that Tan Boon Tin was carrying out in the Asli areas since he came to Ipoh in 1980. Kajang community was one more place he visited, meeting up with old friends like Mr. Ramayah Rengan, and Mr. Jami Subramaniam who was not keeping well.

Kok Hoon and Dr. Kang visiting Theresa Chee in Ipoh, 2009 (Photo credit: Tan Boon Tin)

As his sunset days neared, Kok Hoon could not drive around actively. Yet he followed other friends to where his heart was always – the Asli areas. He would join Mr. Karthikeyam of Subang community for an overnight stay among the Asli people in the village in Keding, near Slim River. Although feeble and tired, he was seen very energetic the moment he addressed the friends.

On the 68th birthday of Kok Hoon, March 2012. Standing L-R: Gwee Goh Yan, Giam Chin Chye, Karthigeyam, Lum Weng Hoe, and Alexson Keling from Miri. Seated next to Kok Hoon is Alpha an Asli believer from Kampung Menderang, very attached to Kok Hoon.(Photo credit: Lum Weng Hoe)

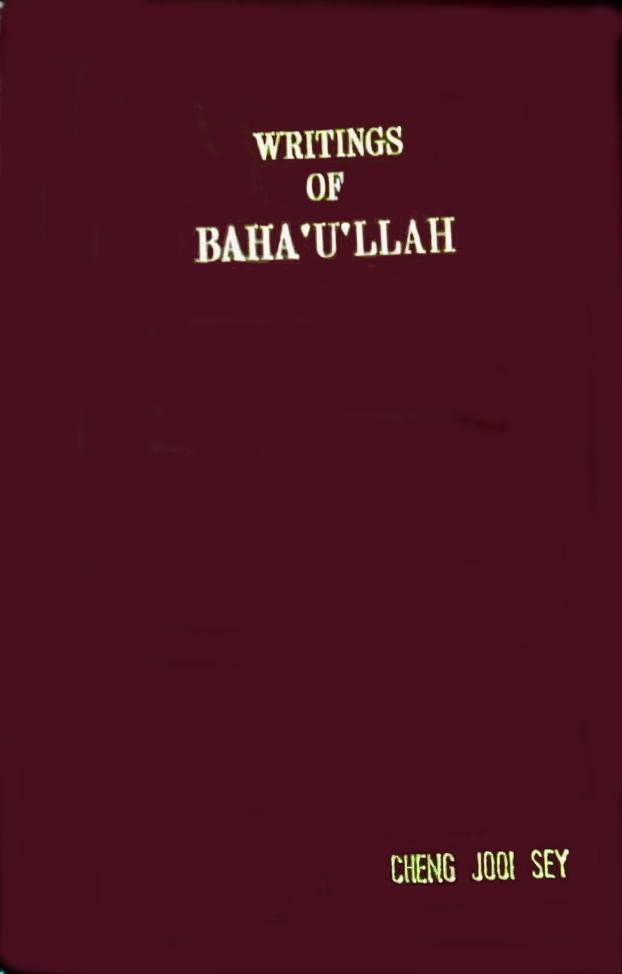

Meanwhile, Kok Hoon had been working for months and compiled photostat copies of his favorite Writings of Bahá’u’lláh but owing to financial difficulties he could not bind them to be distributed to some of his close friends. In 2011, Mr. Jacky Chan and Mr. Goh Kean Kooi from Penang visited him at his residence. At this meeting, Kok Hoon looked very sad on account of his inability to bind a few copies of the compilation. Jacky Chan and Goh Kean Kooi took Kok Hoon in their car to a printer in Petaling Jaya town and worked out the details, and in three weeks’ time the binding was completed with hardcover, and about thirty copies were passed on to Kok Hoon. The title of the book and the names of the intended recipients were embossed in gold color. Kok Hoon was reborn with a new radiance. He sent this Short Message System to Goh Kean Kooi, “So very happy! Bahá’u’lláh arranged everything. Oh! I can’t sleep! Something which troubled me for months through health to near-death is now solved. Thank you. Thanks to the Lord!” These two friends had been visiting Kok Hoon often in the last phase of his life and kept communicating with Kok Hoon by telephone calls and exchange of SMS. Kok Hoon even had been planning to take them for teaching trips to Penang, state of Kelantan and South Thailand, but his ill health took the upper hand to halt him.

One of the recipients of the compilation was Cheng Jooi Sey of Alor Setar.

When Kok Hoon became more and more immobile, he invited friends to visit him at his home. His conversation with believers often centered on the urgency of completing the unfinished goals. One of the very last to visit him was Dr. Gopinath, whom Kok Hoon loved much. When Dr. Gopinath visited him, Kok Hoon was rushing through some brief write-up about himself which he had wanted to be published by someone. That was his last wish, expressed to his dear friend Dr. Gopinath.

The third quarter of the year 2014 was, unfortunately, a painful period of frequent hospitalization for the one time vibrant, enthusiastic, relentless and active worker in the Cause. Kok Hoon developed acute health complications, compounded with serious diabetes with which he had been battling for some years. When gangrene was affecting his leg, he went on a period of intensive exercises, including swimming 20 laps in an Olympic size swimming pool for days and chanting the Tablet of Ahmad from memory several times a day. For no known reasons, he abruptly gave up on intensive exercise and started consuming all kinds of food that were not good for him, defying advice by both doctors and close friends. His health deteriorated faster. On 8 January 2014, Kok Hoon was diagnosed with severe stomach perforated gastric ulcer. After an operation, he was admitted into the ward for 36 days at the Intensive Care Unit of University Hospital and moved to a normal ward for another two weeks. He was discharged with bedsore, with holes under the skin measuring a depth of two forefingers. He continued to get dressing done at home, while still getting in and out of the hospital. Kok Hoon was admitted again for Deep Vein Thrombosis, kidney failure, and irregular heartbeat.

When he was discharged, he expressed intense wish to attend the Bahá’í Winter School in Port Dickson starting 14 December 2014. Jacky Chan and Goh Kean Kooi took him to the Winter School. At that gathering, he indicated to some of his close friends, including G.A. Naidu about his premonition that his days on this earthly plane were ending. On the last day of the Winter School, Kok Hoon was not able to move his legs. Jacky Chan and Goh Kean Kooi carried him into their car and brought him back to his home in Subang Jaya. That was about the last Bahá’í gathering he attended.

On 23 December 2014, he was again admitted to University Hospital. Kok Hoon’s leg was bad with gangrene and needed to be amputated to save his life. But Kok Hoon did not consent to amputation. On 4 January 2014, Kok Hoon’s close friend Lum Weng Hoe from Subang Jaya and his wife Shirley visited Kok Hoon who was already on the oxygen mask. On seeing Lum and Shirley he fought with the nurses to remove the oxygen mask to enable him to chant the Tablet of Ahmad, his favorite prayer, together with Lum and Shirley. Lum and Shirley chanted the prayer with tearful eyes, while tears were rolling down the cheeks of Kok Hoon. After the prayers, Lum and Shirley instinctively moved forward, held Kook Hoon’s hands tightly, kissed them reverently, took a step back and bowed with respect to that unique personage. Kok Hoon waved his hand to bid his final farewell. Then the couple left with a heavy heart. Just before breathing his last, Kok Hoon was still busy sending SMS to some of his friends, oblivious to the reality that his time was almost out and over. He sent SMS to his friend Goh Kean Kooi, “I will get out of the hospital in three days’ time, trying to avoid dialysis. I want to get out and do Bahá’í work.” But the Divine Will was otherwise. On Monday, 5 January 2015, at 6:30 pm, while undergoing dialysis, Kok Hoon’s already weak heart stopped, and his pure soul winged its flight to the Abha Kingdom.

A wake was held at the residence of Kok Hoon in Subang Jaya town. Several friends, Asli friends included, stayed on to say prayers round the clock. The Asli friends said prayers in the Semai language into which Kok Hoon had translated for them under the Nine-Year Plan. They also chanted some favorite prayers of Kok Hoon. A few friends spoke at the funeral. Alpha, the Asli believer from Kampong Menderang said some words in the Semai language. Lum Weng Hoe gave a moving tribute to Kok Hoon. When reading out eulogy on Kok Hoon that the author sent from abroad, Mr. Selvakumar Thambipillai chocked a few times. Emotions ran very high in the gathering.

That was indeed a very befitting funeral arrangement, following which Kok Hoon was given a kingly send off, to be buried at the Nirvana Cemetery in Shah Alam, Selangor. Thus, meaningful and weighty life of more than half a century of illustrious service came to an end!

At this juncture, a word has to be said of his wonderful wife. Mrs. Chow Kim Foong was Kok Hoon’s strongest supporter, giving him all the support and encouragement to serve the Faith. She was a mother-like figure, kind-hearted and always there to provide any assistance she could for her fellow believers. She withstood so many tests with such an indomitable spirit- all armed with the power of prayers and complete faith in her Creator. She loved Kok Hoon not only because he was a good husband, but also because of the amount of love he had for the Faith.

Whither can a lover go but to the land of his beloved? – Bahá’u’lláh

In summing up Kok Hoon’s life, we have to underscore that he was well-endowed with multi-talents. From childhood days, Kok Hoon was highly intelligent, sharp-tongued and quick-minded, coupled with extreme wittiness. Those who had understood him well would call him as an uncut diamond. An uncut diamond is still a diamond! He had the talent to liven up the atmosphere at gatherings. When introducing himself at gatherings held after his retirement, he would say “I am an independent tax consultant. My job is to advise people on how to avoid paying taxes.” It was that kind of wittiness that kept the friends in stitches. He was very quick to detect anything incongruent and would voice out without any fear. It would be difficult, and yet interesting to keep pace with the speed with which his mind would think, and words flow. Somehow, throughout his life, Kook Hoon had demonstrated that he was never suited to the cut and thrust of hypocrisy. His outspoken nature could have upset the equilibrium at some gatherings. All things considered, there were no malicious intentions in him.

One must get to the root of his childhood days to correctly appreciate his sometimes difficult to understand behavior. Child abuse, utter poverty and constant traumatic incidences in his teen life had molded his personality. Kok Hoon never ever had a happy childhood. At the very tender age 10, he was forced to carry a big rattan bag full of Chinese cakes and hit the streets to sell them. Each day Kok Hoon had to get up at dawn, sell the cakes on the streets, return home, have breakfast, dress up and then go to school. Upon return from school, he again continued to sell them on the streets, at times, till dusk. He had to do this to support his impoverished family of 11 children of whom he was the eldest. On several occasions, Kok Hoon also had to go into selling fish and vegetables in the villages and return buying eggs and chickens from there to be sold in the Alor Setar markets. That amount of sacrifice did not help to the fullest. In his next year, when Kok Hoon was 11, the family had to be satisfied with eating only plain porridge. Kok Hoon himself had to sacrifice, on several occasions, his own bowl of porridge to his younger siblings and ended up spending the whole night drinking tap water. As a child, he was abused by parents not out of hatred for him, but owing to frustrations stemming out of extreme poverty. There was an incident he often related. When his parents could not afford a happy atmosphere, he had a loving aunt who cared for him. One day she took him to see the movie “Alexander the Great” at the Alor Setar “Rex” theatre. Upon return, he was beaten up badly.

In 1962 when Kok Hoon was studying in Form 5 and was about to sit for his Senior Cambridge Examinations his father made it very clear that he could not afford to send him to school anymore. That came as a blow to him. That was the time when he often went to the house of a neighbor, mostly on an invitation, for a decent lunch. That neighbor admired the intelligence of Kok Hoon and pitied his plight and predicament. Unasked the kind neighbor offered Kok Hoon RM100 a month to continue schooling until his Senior Cambridge examination was over. And Kok Hoon did well in the examinations. In the mid-1960s, two sons of that neighbor became Bahá’ís and to this day are serving with distinction. Kok Hoon continued to have a rough time at school, not out of bad behavior, but owing to financial problems to support himself. While studying Lower Form 6, Kok Hoon was humiliated and embarrassed when he was made to stand on the school desk, all for not having enough money to pay his school fees. His immediate neighbors at Jalan Menanti, off Jalan Putra (today close to the Setar City Hotel) were Teh Teik Cheow and Teh Teik Hoe who had witnessed with great agony, several of those bitter episodes.

Kok Hoon at left, a master in the Carrom game.

Kok Hoon himself did not forget that kind gesture of the neighbor who had helped him in his school days, which translated into himself helping others. When Kok Hoon was well placed in life, he used to provide similar assistance to students and youths. He himself loved to eat well and had enjoyed taking the unemployed youth and the poor believers for sumptuous meals at good restaurants.

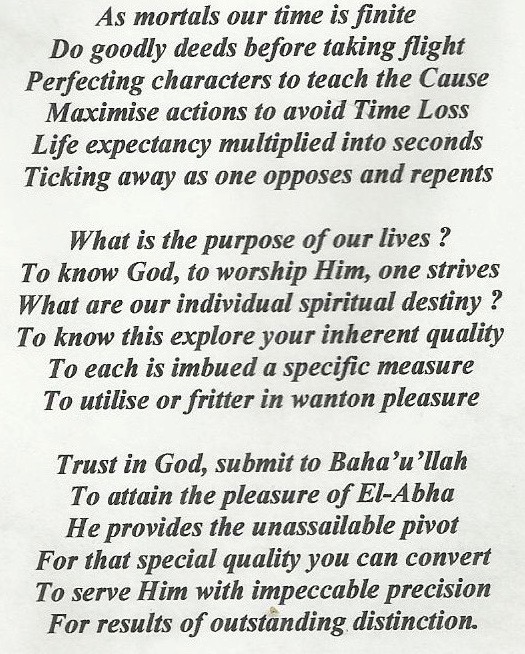

All those bitter and traumatic pasts affected him badly at his last years, at times upsetting his mental framework. Kok Hoon was worn out from what he called “psychological torture in the hands of some authorities.” He used to mention that owing to his active involvement in the Asli areas, he was monitored, his phone lines were tapped, and he was followed wherever he went. But all these were nothing but products of his vain imagination. Despite such utter childhood poverty, God bestowed on Kok Hoon rare talents and extraordinary abilities seldom found in an average student. He developed a superb mastery of the English language even while at college. Kok Hoon’s excellent command of the English language was self-made, perhaps necessitated by his grinding poverty and hardship. He was reading old American newspapers, which his family folded and glued into paper bags to be sold to sundry shops for some meagre income. Kok Hoon read some 50 kilograms of those newspapers every week from the time he was in primary three right up to secondary school. Kok Hoon shone as an unparalleled champion in the Pro-Scrabble game. He loved this game so much that even after retiring from service, he often organized scrabble games for the Bahá’í youths. In all the competitions he was the unparalleled winner. He amazed his competitors by using words which were seldom used in normal conversation and writing. Often his competitors, after losing the game, would quietly consult a dictionary to check out if such words used by Kok Hoon ever existed. Playing scrabble game with him only enhanced the command of the English vocabulary. Kok Hoon used to carry the scrabble board around and organized games or competitions for the Bahá’í youths. In the later part of his life, Kok Hoon joined the Scrabble Society of Malaysia, where his outstanding ability was recognized. He displayed exceptional ability in composing poems of an excellent standard in the English language.

The “Limerick of Lim Kok Hoon” that was published in “SUBANG POST” in 1999

One salient aspect of the Bahá’í life of Kok Hoon was that he was always moving as unrestrained as a wind. Rather than working in committees, he preferred and was seen to be more effective as a loner. He often devised his own plans and would always come out victorious. At times he would disappear from the radar. Then news would reach that he had gone to a far-off community to visit friends. Kok Hoon took serving the Faith very seriously. He created high impacts and traces in all the places he resided. There was always something new he would bring to the communities, and he himself would expect believers to think out of the box. He always pulled a rabbit out of a hat, as they say. His philosophy seemed to be “either shape up or ship out!” Kok Hoon himself created remarkable impacts wherever he resided.

Kok Hoon loved and respected the elders in the Faith. By his own testimony, he had a special liking for several elders, amongst others Theresa Chee of Ipoh, Appu Raman of Kuala Lumpur, S. Nagaratnam of Alor Setar and S. Satanam of Seremban, who had played significant roles in his spiritual growth. Theresa Chee was a mother-like figure for him whose advice he would always cherish. Appu Raman extended Kok Hoon all the love, care, and comforting words whenever he was down in spirit. Nagaratnam had instilled into Kok Hoon immense love for the Holy Writings, making teaching the Faith a life-long activity, facing tests with very strong courage, and avoiding attachment to the kingdom of names. Satanam was one believer who kept encouraging Kok Hoon to teach the Asli people.

Kok Hoon was a person of such rare talents that had he wished to shine in the outside world, he would have excelled in several ways. But Bahá’u’lláh seem to have created Kok Hoon for much greater purposes. When Kok Hoon grew in then Faith, he put aside all his ambitions and accepted serving the Faith as his one and the only prime goal. All things considered, there is compelling and manifest evidence for history to agree that Kok Hoon had carved out a distinctive path of service, undertaken with utter sincerity and strong love for the Blessed Beauty.

“When I became a Bahá’í at age 20, I had decided that I would like to devote my entire life to teaching the Faith and when I drop dead to be buried in any jungle in an unmarked grave. I chose the path of treading on thistles and thorns and I would be content to die penniless. I am very thankful that Bahá’u’lláh had prepared me from age 10 to withstand these pain and suffering for my perfection so that pure and unsullied I shall be able to approach the eternal realm.”- LIM KOK HOON

A. Manisegaran

30 November 2018

Copyright©bahairecollections.com